Rescue operation and subsequent loss of life

Fishing vessel Mucktown Girl and

Canadian Coast Guard ship Jean Goodwill

87.5 nautical miles southeast of Canso, Nova Scotia

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

Just after 2351 Atlantic Standard Time on 11 March 2022, 87.5 nautical miles southeast of Canso, Nova Scotia, the master of the fishing vessel Mucktown Girl reported to the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia, that the vessel was having electrical problems. When the Canadian Coast Guard ship Jean Goodwill arrived on scene, the Mucktown Girl, with 5 people on board, had no power.

With a storm in the forecast, the Jean Goodwill began towing the Mucktown Girl towards the port of Mulgrave, Nova Scotia. Environmental conditions worsened and at 1555 Atlantic Standard Time on 12 March, after approximately 6 hours of towing, the towing operation failed. The Jean Goodwill stood by awaiting improved environmental conditions to reestablish the tow. The next morning, 13 March, the Mucktown Girl began taking on water; the crew donned their immersion suits and abandoned ship into their life raft. With assistance from those on board, 4 crew members boarded the Jean Goodwill from the water. In the difficult conditions, 1 crew member from the Mucktown Girl was unable to board and drifted away. He was recovered from the water by a search and rescue helicopter and taken to the Cape Breton Regional Hospital, where he was pronounced dead. The Mucktown Girl was last sighted at 1139 Atlantic Daylight Time, after which the vessel sank.

1.0 Factual information

1.1 Particulars of the vessels

| Name of vessel | Mucktown Girl | Jean Goodwill |

|---|---|---|

| Transport Canada official number | 827082 | 841978 |

| International Maritime Organization number | Not applicable | 9199634 |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada vessel registration number | 106611 | Not applicable |

| Port of registry | Shelburne, Nova Scotia | Ottawa, Ontario |

| Type | Fishing | Medium icebreaker |

| Gross tonnage | 48.22 | 3849 |

| Registered length | 12.65 m | 77.78 m |

| Built | 2004, Aylward Fibreglass Inc, NS | 2000, Havyard Leirvik AS, Norway |

| Propulsion | 1 diesel engine (336 kW) driving a single fixed-pitch propeller | 4 diesel engines (13652 kW in total) driving 2 variable-pitch propellers |

| Bollard pull | Not applicable | 200 tonnes |

| Crew | 5 | 25 |

| Registered owner and authorized representative* | Border Seafoods Ltd | The Minister of Fisheries and Oceans |

| Recognized organization | Not applicable | DNV |

* The owner and authorized representative, Border Seafoods Ltd, owned 4 other vessels with similar operations. These other vessels were registered at Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, and not Shelburne.

1.2 Descriptions of the vessels

1.2.1 Mucktown Girl

The Mucktown Girl (Figure 1) was of the Cape Island design, built in 2004 from moulded, glass-reinforced plastic. The vessel was designed for lobster fishing and had been adapted to fish halibut using longline.

The wheelhouse was located forward of amidships. The area below the main deck was divided into 4 compartments: the forecastle, which housed the accommodations; the engine room; the fish hold; and the lazarette (aft peak). The vessel was fitted with an aluminum bollard welded to an aluminum base plate that was fixed to the fibreglass forecastle deck.

A 6-person life raft and an emergency position-indicating radio beacon (EPIRB) were both located on the wheelhouse top. The vessel was also equipped with 2 life buoys, 18 pyrotechnic distress signals, and 5 immersion suits.

The Mucktown Girl was purchased by the current owner, Border Seafoods Ltd, in November 2021.

1.2.2 Canadian Coast Guard ship Jean Goodwill

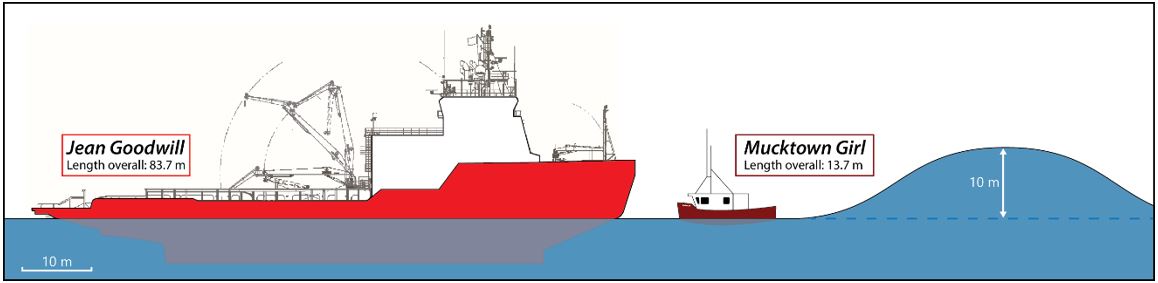

The Canadian Coast Guard ship (CCGS) Jean Goodwill (Figure 2), originally built in 2000, was purchased by the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) in 2020 and converted from an anchor-handling tug supply vessel to a medium icebreaker. The vessel is of closed construction with an all-steel welded ice-strengthened hull.

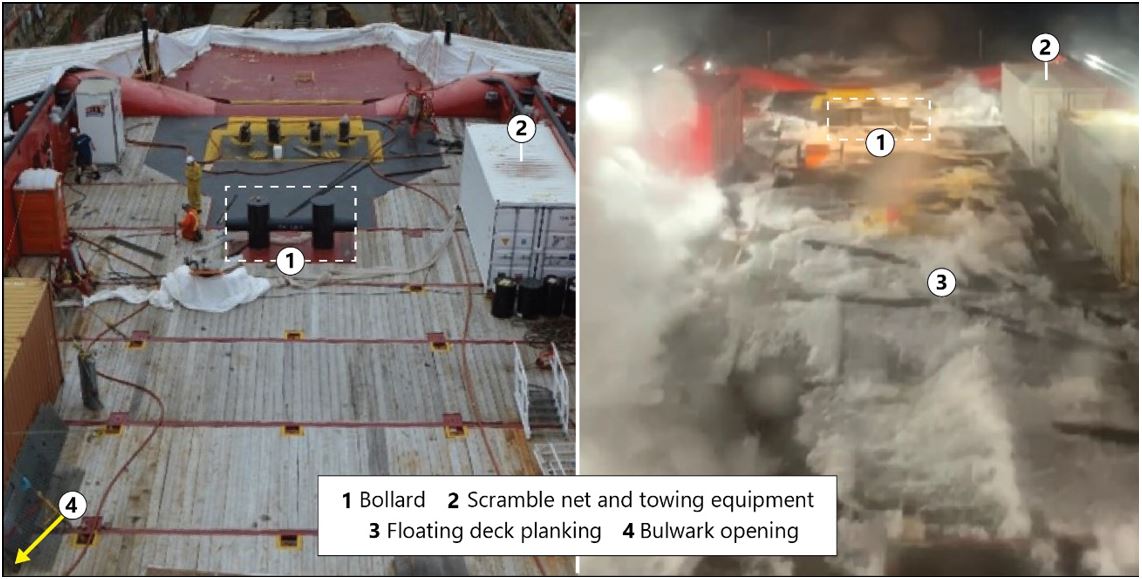

The superstructure is located forward. The aft deck is fitted with a high inner bulwark and the stern is open. Shortly before the occurrence, the aft deck had been refitted with wood planking over the steel deck.

Three 20-foot shipping containers are fixed to the main deck aft, housing the pollution response, towing, and search and rescue (SAR) equipment (Figure 3). During towing operations, the towline is manually removed from the container and connected to the double cross towing bollard on the main deck aft, then passed through the towing pins.

The scramble net (Figure 4), stored in a shipping container on the main deck aft, is made of polypropylene rope and aluminum. When deployed, the scramble net must be carried across the main deck and through a small opening in the bulwark, then attached to the outboard side of the bulwark just aft of the superstructure. At this point, the freeboard is about 1.5 m.

1.3 History of the voyage

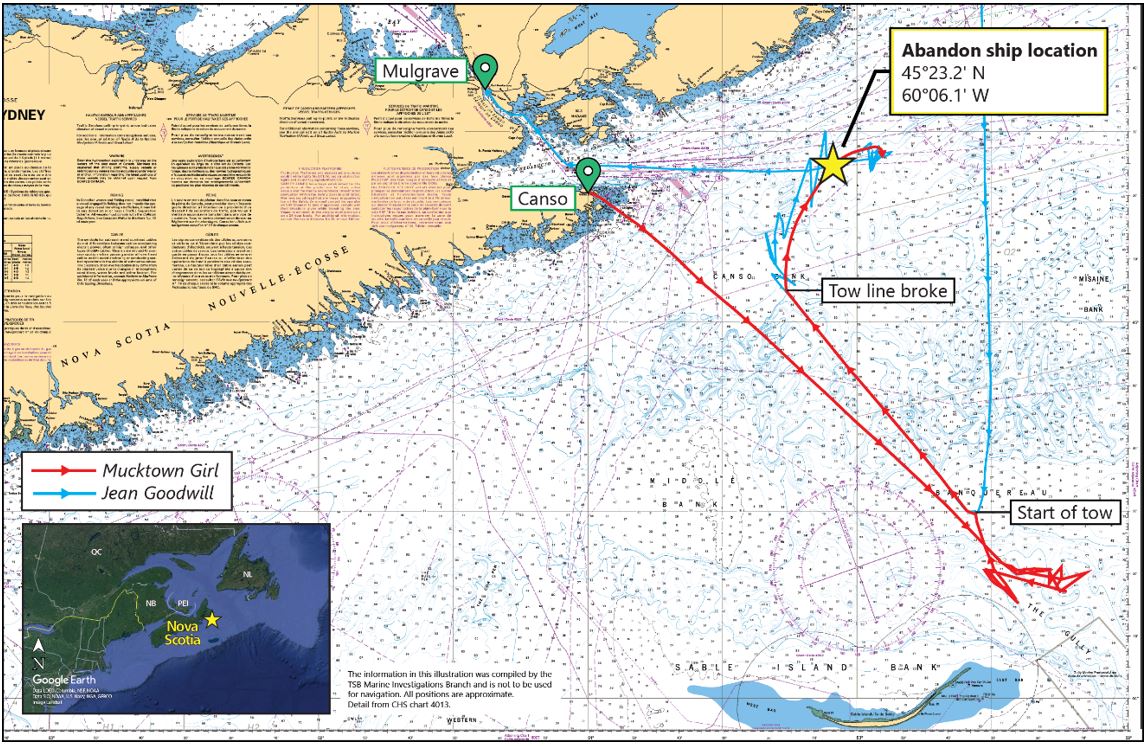

On 09 March 2022, the fishing vessel Mucktown Girl departed Canso, Nova Scotia, with 5 crew members on board to fish halibut (Figure 5). On 11 March, the crew headed back to Canso to unload their catch and reach shelter ahead of a forecast storm.

Just after 2351,All times in the report are in Atlantic Standard or Daylight Time. The change from Atlantic Standard Time (Coordinated Universal Time minus 4 hours) to Atlantic Daylight Time (Coordinated Universal Time minus 3 hours) happened at 0300 on 13 March, during the course of the occurrence. when the Mucktown Girl was 87.5 nautical miles (NM) southeast of Canso, the master called the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (JRCC) in Halifax, Nova Scotia, via satellite phone to report having electrical problems and to request a tow. JRCC issued a maritime assistance request broadcast (MARB) but received no response. JRCC then tasked the Jean Goodwill to assist. On 12 March at 0029, the Jean Goodwill departed Sydney, Nova Scotia.

At 0300, a storm warning was issued by Environment and Climate Change Canada for the area (Eastern Shore, Sable, and Fourchu). Winds were forecast to be from the south and increase to 50 knots by the evening.

On the voyage to the Mucktown Girl, which took approximately 7 hours, the master of the Jean Goodwill reviewed records from a previous successful tow of the Mucktown GirlThe Jean Goodwill had successfully towed the Mucktown Girl on 06 February 2022 from 144 NM SSE of Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, to Louisbourg, in winds from the north at 5 knots with 1 m seas (TSB marine transportation safety investigation M22A0026). and reviewed the risks of the operation using the CCG standard risk assessment for towing (referred to in this report as “the Canadian Coast Guard risk register;” see Appendix A for details). In preparation for the towing operation, a 212 m towline was shackled to a 90 m mooring line to increase the length of line available.

At 0913, the Jean Goodwill reached the Mucktown Girl. By this time, the Mucktown Girl was without powerWithout power, a vessel has limited pumping capacity, lights for navigation and visibility, and communications. It is also difficult to control the vessel direction with respect to the waves. For these reasons, some classes of vessel are required to have emergency sources of power; however, an emergency power source was not required on the Mucktown Girl. and the winds were from the south at 15 to 20 knots. Crew members from the Jean Goodwill delivered 2 portable very high frequency (VHF) radios and 2 batteries, using the vessel’s fast rescue craft (FRC). The master of the Mucktown Girl requested that the Jean Goodwill tow the vessel as fast as possible because of the approaching storm.

At 0935, a towline was connected from the main deck bollard of the Jean Goodwill to a bollard on the Mucktown Girl’s forecastle deck (Figure 6), and the towing operation began at a speed of 8 knots. Shortly after, the CCG’s towing waiverCanadian Coast Guard, Policy and Operational Procedures on Assistance to Disabled Vessels, Appendix 1: Towing Conditions and Understanding, at https://www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca/publications/search-rescue-recherche-sauvetage/disabled-vessels-navire-panne-eng.html (last accessed 28 October 2024). (Appendix B) was read over the VHF radio to the master of the Mucktown Girl.

At 1005, the towing speed was increased to 9 knots, and the winds were from the east-southeast at 20 to 25 knots. At that speed, the Mucktown Girl began to yaw,When a vessel yaws, the bow moves from side to side instead of straight on in the direction of travel. and the towing speed was reduced back to 8 knots almost immediately. The towing operation continued for approximately 5 hours at speeds of between 8 and 10 knots.

At 1555, the bollard on the Mucktown Girl broke and the towing arrangement failed. The break in the bollard occurred at the aluminum weld where the bollard met the base plate. At this time, the winds had increased to 30 to 35 knots with 2.5 m seas. The master of the Mucktown Girl reported to the master of the Jean Goodwill that the vessel was managing in the sea conditions.

At 1643, the master of the Jean Goodwill and JRCC discussed reconnecting the towline by attaching a sling to the bow of the Mucktown Girl but concluded that this option would cause further damage to the smaller vessel. The winds had changed to south-southeast and increased to 40 to 45 knots, with 4.5 m seas. At 1652, JRCC contacted the CCGS Spindrift, which was in port at Louisbourg, Nova Scotia. Because the Spindrift would not have been able to tow successfully in the deteriorating sea conditions, JRCC and the master of the Spindrift decided that the Spindrift would remain in port. JRCC also hailed a fishing vessel in the area about taking over the tow but did not receive a response.

At 1721, JRCC tasked the Jean Goodwill to stand by until conditions improved and the tow could be re-established, and the crew of the Jean Goodwill left the towline ready on deck. The master of the Jean Goodwill agreed to check in with the Mucktown Girl every hour by VHF radio, and the master of the Mucktown Girl continued to report that everything was okay.

At 2029, JRCC was informed that one of the crew members of the Mucktown Girl had phoned a family member. The crew member was concerned about the vessel’s ability to survive the night in the bad weather but that everything was okay at that time.

By 2241, winds were from the south, directly onto shore, at 50 to 55 knots with 8 m seas. The Jean Goodwill’s aft deck was awash, and some of the wooden deck planks were floating free. The Mucktown Girl was 24 NM from shore and was drifting north toward land at 2 knots.The time it would take the vessel to reach shore at this speed is short enough and the distance from shore close enough that if environmental conditions are poor or additional resources are not available, an emergency situation could develop quickly. Concerned that the storm might run the vessel aground, JRCC and the master of the Jean Goodwill discussed options for evacuating the crew of the Mucktown Girl using the Spindrift, the FRC, or a SAR helicopter. Winds were forecast to shift west, which would likely prevent the Mucktown Girl from drifting toward land. Ultimately, JRCC and the master of the Jean Goodwill decided that the Jean Goodwill would continue to stand by and monitor the vessel’s drift. In these weather and sea conditions, a vessel the size of the Mucktown Girl was a poor radar target (Figure 7).

At the check-in at 0038, the master of the Mucktown Girl confirmed that everything was still okay. The weather conditions continued to worsen, and by 0100 the seas were high enough that the master of the Jean Goodwill had to manoeuvre both to keep a safe distance of a few NM from the Mucktown Girl and to avoid the effects of beam seas.Vessels travelling in a beam sea encounter waves at approximately 90° relative to their heading. These conditions create large roll angles and increase the amount of water shipped on deck.

By 0300,This time is Atlantic Daylight Time (UTC minus 3 hours). Times from this point onwards are in Atlantic Daylight Time, unless otherwise noted. the Jean Goodwill was approximately 5 NM away from the Mucktown Girl. Winds were from the south at 40 to 50 knots, with 8 to 10 m seas. At their next check-in, the master of the Mucktown Girl reported to the Jean Goodwill that the vessel was stable. To allow the crew of the Mucktown Girl to rest, the period between check-ins was extended.

At 0558, the Jean Goodwill called the master of the Mucktown Girl to check in, and he reported that everything was okay. Seven minutes later, at 0605, the master of the Mucktown Girl called the Jean Goodwill to report 1.5 feet of water on the aft deck. The Jean Goodwill immediately turned and headed at full speed toward the Mucktown Girl. At this point, the vessels were approximately 3.5 NM apart.

By 0611, winds were from the southwest at 45 to 50 knots with 8 to 10 m seas, heavy rain, and dense fog. The Mucktown Girl had begun to sink. Crew members donned immersion suits, intending to abandon ship directly into the sea. The master of the Mucktown Girl informed the Jean Goodwill of the crew’s intentions via VHF radio; the Jean Goodwill advised the master to prepare the life raft.

At 0619, JRCC requested helicopter support, and at 0621, a Mayday relay was broadcast from the Jean Goodwill.

At approximately 0627, the crew of the Mucktown Girl entered the life raft, which remained attached to the vessel by a painter. While en route to the Mucktown Girl, crew members on the Jean Goodwill were called out on deck. Each crew member chose where to go and help as they arrived. They removed the scramble net and the Jacob’s ladderA Jacob’s ladder is a flexible hanging ladder composed of vertical rope or chain and horizontal wooden or metal rungs. from the port storage container and moved them across the deck and through the inner bulwark on the starboard side (Figure 4). As they attached the scramble net to the cleats, they experienced some difficulty because the net washed back on board repeatedly. The Jacob’s ladder was secured beside the scramble net. Some of the deck planking was floating free and the deck was awash with debris.

At 0630, the Jean Goodwill approached closely enough to observe that the life raft was attached to the Mucktown Girl. The Jean Goodwill attempted to contact the crew via VHF radio several times but received no response.

At 0641, a crew member of the Mucktown Girl cut the painter attaching the life raft to the vessel, and the life raft began to drift away from the sinking vessel. While they were in the life raft, Mucktown Girl crew member 3 told another crew member that water had entered his immersion suit.

The master of the Jean Goodwill attempted to position the vessel so that the crew members in the Mucktown Girl’s life raft could access the scramble net. At 0650, the seas were more than 10 m, and the Jean Goodwill encountered a large wave that caused a roll of more than 30 degrees. In the wheelhouse, a crew member was injured when he fell. On the main deck, the chief officer was seriously injured when he was swept against the inner bulwark. As well, several crew members were nearly washed overboard. Once the bridge team had learned of the chief officer’s injury, an announcement was made over the vessel’s intercom calling all available crew to the deck.

At 0651, the Spindrift left the CCG station in Louisbourg. At 0653, a Cormorant SAR helicopter was tasked from Canadian Forces Base Greenwood, Nova Scotia.

By 0658, the Jean Goodwill was approximately 5 m from the life raft. Suddenly, crew member 1 jumped from the life raft into the water. He made several attempts to climb the scramble net. At 0705, he was brought on board with the help of the Jean Goodwill crew.

The Jean Goodwill was repositioned 3 to 5 m away from the life raft; without waiting for instructions from the Jean Goodwill, crew member 2 jumped from the life raft into the water, climbed up the scramble net with assistance, and was recovered at 0726.

At 0728, the Jean Goodwill was repositioned. Without waiting for instructions from the Jean Goodwill, crew members 3 and 4 jumped into the water at the same time. Crew member 4 grabbed hold of the scramble net while crew member 3 grabbed the Jacob’s ladder. Both crew members were hit by a wave, thrown back into the sea, and then drifted toward the life raft. The master of the Mucktown Girl, who was still in the life raft, was able to grab hold of both crew members. He helped crew member 4 into the life raft but lost hold of crew member 3, who drifted toward the Jean Goodwill’s stern.

The Jean Goodwill crew attempted to throw a line to crew member 3 as he drifted, but winds made it difficult and the crew member did not respond. At 0733, a heaving line was thrown from the Jean Goodwill to the life raft; the master tied the heaving line around crew member 4, who was then pulled on board.

The Jean Goodwill was repositioned in preparation for rescuing the master of the Mucktown Girl. The master jumped from the life raft into the water and swam to the scramble net; he climbed the net and was brought on board at 0758.

At 0843, 2 self-locating data marker buoys were thrown from the Jean Goodwill to help focus the search for the missing crew member, but they did not function.

At 1129, the helicopter arrived on scene and began the search for the missing crew member. The Mucktown Girl was last sighted at 1139, after which the vessel sank.

At 1226, the helicopter located the missing crew member. He was retrieved at 1231 and was transported to the Cape Breton Regional Hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

1.4 Environmental conditions

On 12 March at approximately 1000 Atlantic Standard Time, when the towing operation had just begun, the air temperature was near 4 °C and the water temperature was near 1 °C. Winds were east-southeast at 20 to 25 knots and seas were 1 to 2 m. A storm warning was in effect, with winds forecast at 40 to 50 knots from the south, periods of rain or snow, and a risk of thunderstorms.

At 1555 Atlantic Standard Time, when the bollard on the Mucktown Girl broke and the tow failed, the winds had increased to 30 to 35 knots from the east-southeast with 2.5 m seas. The storm had not yet peaked.

At 2241 Atlantic Standard Time, when JRCC staff and the Jean Goodwill crew discussed removing the crew from the Mucktown Girl, the winds were from the south, directly onto shore, at 50 to 55 knots with 8 m seas.

On 13 March at approximately 0600 Atlantic Daylight Time, just before the crew of the Mucktown Girl abandoned ship, the peak of the storm had passed. The air temperature was near 12 °C and the water temperature was near 4 °C. Winds were southwest at 45 to 50 knots and seas were 8 to 10 m. Sunrise was at 0732.

1.5 Vessel certification

1.5.1 Mucktown Girl

The Mucktown Girl was required to undergo a periodic Transport Canada (TC) inspection for certification every 4 years. It had last been inspected on 24 November 2020 and its inspection certificate for Near Coastal, Class 1 voyages was extended to 13 October 2024.

1.5.2 Canadian Coast Guard Ship Jean Goodwill

The Jean Goodwill was enrolled in TC’s Delegated Statutory Inspection Program. DNV conducted the vessel’s last annual inspection on 29 June 2021 and the vessel’s last 5-year (renewal) inspection on 17 November 2020.

1.6 Personnel certification

1.6.1 Mucktown Girl

The master of the Mucktown Girl held a Fishing Master, Fourth Class certificate of competency issued on 20 May 2014 and renewed in 2020. He had completed Marine Emergency Duties (MED) with respect to Basic Safety in 2015 and held a Restricted Operator Certificate – Maritime Commercial (ROC-MC) issued in 2014.

The mate held a certificate of serviceCertificates of service were issued to fish harvesters with a specified amount of experience before July 2007. These certificates were accepted in place of formal training and assessment. as master of a fishing vessel of up to 15 gross tonnage or not more than 12 m in length, issued on 28 April 2021, a MED Domestic Vessel Safety certificate issued in 2018, and a ROC-MC issued in 2014.

The 3 other crew members on board did not hold any certification or have any MED training. The occurrence voyage was the first voyage on the Mucktown Girl for these 3 crew members.

The safe manning document required the mate to have certification for a vessel of up to 24 m, 1 other crew member to have at least MED basic safety, and additional watchkeeping for overnight voyages.

1.6.2 Jean Goodwill

The chief officer held a Chief Mate, Near Coastal certificate first issued in 2016 and renewed in 2021. He was on his 4th rotation on the Jean Goodwill. He had served with the CCG for 13 years, mostly on the larger CCG vessels.

The first officer held a Watchkeeping Mate certificate first issued in 2013 and renewed in 2018. He was on his 4th rotation on the Jean Goodwill.

1.7 Towing a vessel

Towing is a common operation. It is simple in principle but the range of conditions and the forces that act during a towing operation mean that planning for contingencies is important.

Five weeks before the occurrence, the Jean Goodwill had towed the Mucktown Girl for approximately 19 hours at an average speed of approximately 6.0 knots in light winds and seas.TSB Marine Transportation Safety Occurrence M22A0026. The Mucktown Girl has been involved in 5 other marine transportation safety occurrences in the last 10 years: M21A0148, M15A0402, M14A0456, M14A0042, and M13M0087. This was the only time that the Jean Goodwill had towed a vessel since entering service with the CCG.

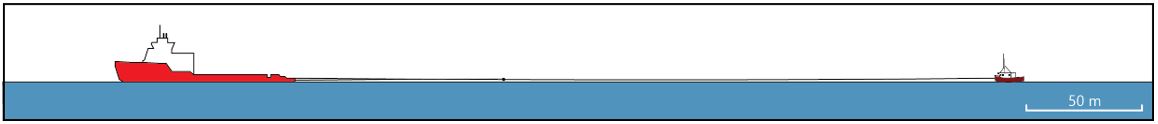

1.7.1 Forces that act during a tow

During a tow, constant forces act on the towed vessel and the towing vessel at the points where the towline is attached. Shock forces, which can vary suddenly, act on the vessels as they get underway and as their relative speeds change because of waves and winds. Both constant and shock forces may be different in magnitude from the forces that act on a vessel moving under its own power. These forces may also differ in the points where they act on the vessel. Most of these forces come from the power of the towing vessel. Some forces come from the reactions of the 2 vessels to waves and winds: when the towing vessel is much larger than the towed vessel, these forces affect the smaller vessel much more. As described in the CCG Towing Guide, when a large vessel tows a smaller vessel, the risks to the smaller vessel of capsizing, towing gear damage from towing action, and a parting towline are higher than for like-sized vessels, as are the risks associated with icing, sea conditions, shock loading, and rapid and violent yawing.Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Canadian Coast Guard, CCG Towing Guide (March 2013), p. 37. The CCG guidance treats towing in ice as a separate case for risk assessments. Much of this guidance was developed in response to the capsizing of the L’Acadien II (TSB Marine Investigation Report M08M0010).

When the towed vessel is much smaller than the towing vessel, shock forces on the towing arrangement can be very large. Increasing the towline sag (catenary) by lengthening the towline increases the amount of the shock forces that can be absorbed by the towline instead of passing them to the towed vessel.

The forces acting during a towing operation are unpredictable, especially in an emergency where there is less control over the conditions; the risk of a tow operation failing is always present. It is good practice to identify the weakest point in the towing arrangement and where possible ensure that this weakest point is in the towline and not a part of the towed vessel or the towing vessel.Ibid., Chapter 6: Guidance on Length of Towline, pp. 27–28. For example, IMO guidelines recommend that the other parts of the towing arrangement have a minimum breaking load of 1.5 to 2 times the breaking load of the towline.International Maritime Organization, MSC/Circ. 884, Guidelines for Safe Ocean Towing (December 1998), subsection 12.15.

Towing best practices and standards are typically focused on the towing vessel.

1.7.2 Towing operations and contingency planning

Before a towing operation begins, the masters of both vessels should agree on a plan for towing. As well, CCG policies require that communication between the bridges of both vessels and the bridge and deck of the towing vessel be maintained. Typically, the master of the vessel to be towed identifies the towing point. A crew member on the towing vessel may perform a visual inspection of this point from a distance.

It is also good practice, especially in an emergency, to have contingency plans already prepared for any high risks that are anticipated.Shipowners’ Mutual Protection and Indemnity Association, Tugs and Tows – A Practical Safety and Operational Guide, (2015), at https://shp-13383-s3.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/media/5416/8667/7299/PUBS-Loss-Prevention-Tug-and-Tow-Safety-and-Operational-Guide_A5_0715.pdf (last accessed 12 November 2024). See also International Maritime Organization, MSC/Circ. 884, Guidelines for Safe Ocean Towing (December 1998), subsections 6.1 and 6.2. Factors to consider include

- the relative size of the vessels;

- power (bollard pull) of the towing vessel;

- weather and sea conditions (including forecast conditions for the duration of the tow);

- proximity to shore, shoals, and other hazards;

- intended towing speed, which is limited by the hull speedThe hull speed is the speed at which the standing wave created by the movement through the water is approximately equal the vessel’s length. Speeds above the hull speed require exponentially more power and can create a dangerously high bow wave and trim where stability and steering are negatively affected. of the vessel being towed as well as the conditions;

- length of towline—the shorter the line, the more shocks occur in the towing arrangement;

- lookout on the towed vessel; and

- the condition of the towed vessel.

When the vessel to be towed is disabled, CCG policies recommend providing the disabled vessel with an alternative means to communicate, for example a portable radio. Whether to also supply other equipment, such as pumps or temporary lights, is at the discretion of the CCG master.

1.7.3 Towing points on fishing vessels

Fishing vessels often perform tows and are towed. Most fishing vessels connect the towline to a bollard located on the forecastle deck when being towed; however, the primary purpose of the bollard is to serve as a tie-up point when alongside. Such bollards are typically constructed of aluminum or steel and are bolted to the deck (if the deck is fibreglass, fibreglass over wood, or wood) or welded to the deck (if the deck is steel or aluminum). Unlike bollards on docks or on larger vessels, such bollards are not tested and marked with a safe working load.

Finding: Other

There are no Canadian standards or regulations for the design, construction, and inspection of towing points of fishing vessels.

1.8 Search and rescue equipment and drills

Vessels that respond to emergencies and carry out rescues have emergency equipment requirements specific to their roles.

CCG vessels are required to carry SAR equipment and to keep it well maintained.Canadian Coast Guard, Canadian Coast Guard Order 207, CCGO 207 – Search and Rescue Equipment on Board Canadian Coast Guard Vessels (revised 12 January 2022). The minimum equipment required for all types of CCG vessels includes first aid equipment and items such as portable pumps, portable VHF radios, and self-locating data marker buoys. The smaller, dedicated SAR vessels are required to carry additional equipment, such as a horseshoe collar and line (also known as a life sling) and a line-throwing device. Larger vessels such as the Jean Goodwill are also required to carry at least 1 line-throwing device, as well as 2 scramble nets. The larger vessels are not required to carry any equipment that can be used to retrieve unconscious persons directly from the water. Instead, the person would be retrieved into an FRC or other vessel with a lower freeboard.

At the time of the occurrence, the Jean Goodwill was carrying all the equipment required by the CCG except for 1 of the 2 scramble nets.

Different industries may have different requirements for SAR equipment. For example, because of the nature of the oil and gas industry, standby vessels that support the offshore oil and gas installations must meet detailed contractual requirements. Such vessels must be capable of safely recovering survivors from the water as well as from an installation. One requirement is that they must have a powered survivor rescue device, such as a rescue scoop, that can retrieve unconscious persons directly from the water, as well as climbing aids such as a scramble net.Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board and Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board, Atlantic Canada Standby Vessel Guidelines, Second Edition (14 June 2018), subsection 2.2: Survivor Rescue Equipment, p.12.

1.8.1 Emergency drills

Emergency drills that include realistic scenarios increase a crew’s preparedness, readiness, and effectiveness in the event of an emergency. Realistic scenarios might include different conditions, such as darkness, noise, missing crew members, or damaged equipment, or combinations of individual scenarios.

On the Jean Goodwill, person overboard drills were the only water rescue drills regularly performed. In a person overboard drill, the 3 parts of the drill are to keep the person in sight (and provide them with assistance where possible), to bring the vessel back to the person safely, and to retrieve the person from the water. These drills were done annually for each crew rotation as required by the CCG safety management system (SMS).

In contrast, standby vessels in the oil and gas industry are required to conduct frequent and realistic drills and periodic trials to maintain a high level of preparedness. For example, in the case of FRC drills, “frequent” means at least twice per crew rotation and not less than twice per month.Ibid., subsection 4.6.2: FRC Drills.

1.8.2 Rescue equipment for persons overboard

For a person to be successfully retrieved from the water, they must be raised to the height of the vessel’s freeboard and protected from movement of the vessel and water. Retrieval is more difficult if the person is experiencing cold incapacitation, is injured, or is wearing bulky gear such as an immersion suit.

Equipment used to climb from the water to the deck includes Jacob’s ladders and scramble nets. Equipment used to transfer personnel from the water to the deck includes davit systems, rescue scoops, and rescue slings. Some of this equipment requires the person to be able to climb independently. Other devices, such as rescue davits, may require 2 operators.

Many classes of vessel have requirements for emergency equipment of various kinds for emergencies related to their own vessel and crew, but there are no Canadian marine regulatory requirements for vessels that are carrying out SAR operations.Ibid., section 2: Emergency Response Equipment and Arrangements. TC’s TP 14530, Guidelines for the construction and inspection of pilot vessels (July 2006), recommends that pilot boats carry a mechanical device for retrieving an unconscious person from the water. In Atlantic Canada, contract requirements mean that vessels used in the offshore oil industry (offshore support vessels and anchor-handling tug supply vessels) are equipped with rescue scoops.

1.8.3 Scramble nets

Scramble nets should be fixed in the location where they will be deployed, properly weighted so that they will not wash on board in rough seas, and be easy to grasp. Some models of scramble nets are designed with rigid bars instead of netting and may be permanently fixed to a rescue zone on the vessel. A scramble net with rigid bars provides much better footing and “offers a substantial improvement for maritime self-rescue.”Fisheries and Marine Institute of Memorial University of Newfoundland, Comparison Between Rigid Climbing Aids and Rope Scramble Nets in the Effectiveness of Rescue Operations: A Technical Report submitted to the Canada-Nova Scotia / Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Boards (October 13, 2021), at https://www.cnlopb.ca/wp-content/uploads/news/CBRCARSNERO.pdf (last accessed 15 October 2024). The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) standards for the recovery of persons from the waterInternational Maritime Organization, International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), 1974, as amended, Chapter III, Regulation 17.1. define requirements for scramble nets.

1.9 Immersion suits

Immersion suits are designed to keep a person buoyant, warm, and dry. They can reduce the effects of cold-water shock, delay the onset of cold incapacitation and hypothermia, and prevent drowning. Immersion suits are not effective if water can enter. Water may enter a suit because the suit is not fully donned and zipped, does not fit properly, or is damaged.

When SAR responders recovered the missing crew member, they found that his immersion suit had filled with water.

The immersion suit was not available to the TSB for examination.

1.10 Canadian Coast Guard

As part of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), the CCG is the civilian maritime operational arm of the Government of Canada. The CCG operates many vessels and is responsible for providing maritime resources in support of SAR in federal areas of responsibility. In this role, the CCG works with the coordinated aeronautical and maritime SAR system, which is managed by the Canadian Armed Forces and includes the JRCCs.

In addition to SAR, the CCG provides other services, such as icebreaking, marine navigation, marine communications and traffic, and supports for other DFO programs.

During a SAR operation, the CCG’s first consideration is to protect the lives of all those in danger, whether they are on a vessel in distress or imminent distress, or in the water.Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Canadian Coast Guard, Policy and Operational Procedures on Assistance to Disabled Vessels, Section 3: Guiding Principle, at https://www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca/publications/search-rescue-recherche-sauvetage/disabled-vessels-navire-panne-eng.html (last accessed 15 October 2024). Additionally, the CCG may also help people on disabled vessels when requested. The nature and extent of the help will depend on risks to the persons in need of help, the vessel, and the CCG and its employees.Ibid. The CCG SAR objectives include minimizing property damage, and the CCG will protect the vessels themselves if possible.

1.10.1 Requests for assistance

Typically, a request for CCG assistance comes to JRCC after a vessel has requested help, either through a Marine Communication Traffic Services (MCTS) station or directly. The nature of the response depends in part on whether a vessel is identified as being in distress or disabled according to the following definitions:

Distress A search and rescue incident where there is a reasonable certainty that one or more individuals are threatened by grave and imminent danger and require immediate assistance.

[…]

Disabled A situation wherein a vessel afloat is not in distress or immediate danger, has lost all means of propulsion, steering or control to such a degree as to be incapable of proceeding to safety without assistance.Ibid.

The definition of ‘distress’ is based on whether lives are at risk or at imminent risk. In practice, JRCC and the CCG also consider the condition of the vessel for classifying the situation and vessel as being in distress. In this occurrence, JRCC did not reclassify the incident from a disabled vessel to a vessel in distress until the Mucktown Girl began to take on water and the crew was preparing to abandon ship.

If it is determined that a vessel is in distress, suitable SAR units are tasked. If the vessel is disabled, other options are considered, including, for example, commercial towing or the availability of any nearby vessels willing and able to assist. If commercial assistance is available, then the CCG is not permitted to go to a disabled vessel;Ibid. in practice, commercial assistance is rarely available in the Atlantic region.

For small fishing vessels operating in open water in Eastern Canada, experience has shown that assistance options are essentially limited to CCG and CCG auxiliary vessels. Commercial towing is not generally available, and CCG vessels are routinely tasked to assist disabled vessels as well as vessels in distress or imminent distress. CCG towing operations are reported in disabled vessel SAR calls. Nearly all such calls are closed as either successful tows or on-site repairs. In the 5 calendar years before the sinking of the Mucktown Girl, 2017 to 2021, 1380 SAR calls reported to the TSBNot all SAR calls are required to be reported to the TSB. For example, SAR calls involving pleasure craft are not recorded in TSB data. Incidents are required to be reported to the TSB as per subsection 3(1) of the Transportation Safety Board Regulations. in the Atlantic Region included a request for towing. Of these, 984 (71%) were from fishing vessels. Most of these reports were related to engine problems, fuel, steering, and fouled propellers.

The final decision to tow is made by the masters of the CCG vessel and the vessel that is disabled or in distress. JRCC requests may specify towing, and JRCC staff may offer advice.

1.10.2 Maritime occupational health and safety

Following the occurrence, the CCG completed an internal investigation into the injuries on board the Jean Goodwill, in accordance with requirements under section 276 of the Maritime Occupational Safety and Health Regulations and section 135 of the Canada Labour Code.

1.10.3 Risk assessment processes

Assisting a disabled vessel, including offering spare parts and engineering advice or towing the vessel, and removing crew from a vessel all carry some degree of risk. The master of the CCG vessel evaluates options based on their experience; advice from CCG officers, crew, and JRCC staff; information provided by the master of the disabled vessel; and CCG guidance.CCG guidance and procedures include the Canadian Coast Guard Towing Guide; Policy and Operational Procedures on Assistance to Disabled Vessels; Fleet Safety Manual 7.A.1 – Assessing Risk; the Fleet Safety Manual 7.D.1 – Search and Rescue Operations; Fleet Safety Manual 7.C.4 – Towing Operations; and ship-specific work instructions.

CCG guidance includes steps for reviewing risks of common operations that are listed in a risk register. This risk register was developed as part of a hazard prevention program to assess risk to CCG personnel.Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Canadian Coast Guard, OC 13-2016, Operations Circular: Compliance to Maritime Occupational Health & Safety Regulations, Part 7 – Hazard Prevention Program: National Vessel Risk Register (July 2016). The risk register contains a towing sheet (Appendix A), describing common workplace hazards that may occur as a towing operation is being set up or during the tow and that may affect the CCG crew only. That is, it does not include hazards related to the crew on the towed vessel. The risk register contains blank columns for control measures, action plans, and monitoring actions. These columns may be filled in for a specific operation if needed.

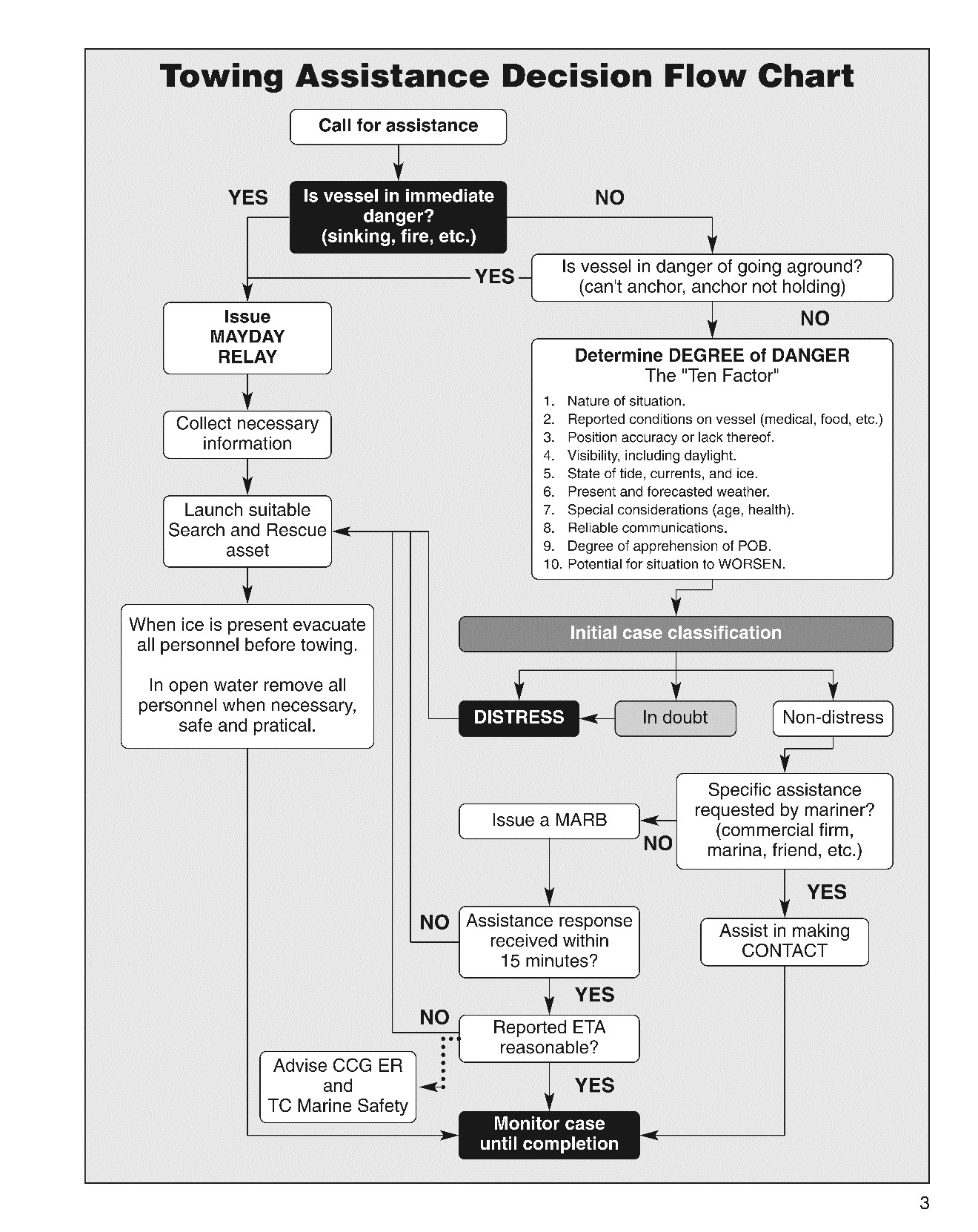

As part of the discussion between the CCG master and the master of the vessel to be towed, which usually includes a discussion of risks, a towing waiver is signed or read over the radio. The towing waiver may be accompanied by a towing assistance decision flow chart. Unlike the presence or absence of iceAccording to the Canadian Coast Guard’s Policy and Operational Procedures on Assistance to Disabled Vessels, at https://www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca/publications/search-rescue-recherche-sauvetage/disabled-vessels-navire-panne-eng.html (last accessed 15 October 2024), the CCG is not to tow vessels of less than 33 m in ice when persons remain on the towed vessel. This policy was developed as a response to the 2008 occurrence involving fishing vessel L’Acadien II (TSB Marine Transportation Safety Investigation Report M08M0010). and the response time of 15 minutes, many decisions in the flow chart are qualitative in nature (necessary, reasonable, potential to worsen, and so on).

Towing assistance decision flow chart

Step 1: Call for assistance is received.

Step 2: Is the vessel in immediate danger? (sinking, fire, etc.)

Step 3: If yes,

- Issue MAYDAY RELAY.

- Collect necessary information.

- Launch suitable search and rescue asset.

- When ice is present, evacuate all personnel before towing. In open water, remove all personnel when necessary, safe, and practical.

- Monitor case until completion.

Step 4: If the vessel is not in immediate danger, is it in danger of going aground? (can’t anchor, anchor not holding)

If yes, follow the process in Step 3.

If no, determine the degree of danger (the “ten factor”):

- Nature of situation

- Reported conditions on vessel (medical, food, etc.)

- Position accuracy or lack thereof

- Visibility, including daylight

- State of tide, currents, and ice

- Present and forecasted weather

- Special considerations (age, health)

- Reliable communications

- Degree of apprehension of POB (persons on board)

- Potential for situation to worsen.

Step 5: initial case classification

Step 6: If the initial case classification is “non-distress”, has specific assistance been requested by mariner (commercial firm, marina, friend, etc.)?

If yes, assist in making contact and monitor case until completion.

If no, issue a MARB (Maritime Assistance Request Broadcast).

Step 7: If a MARB is issued, is the assistance response received within 15 minutes?

If yes, is the reported estimated time of arrival reasonable?

If yes, monitor case until completion.

1.10.4 Towing guidance

The CCG Fleet Safety ManualFisheries and Oceans Canada, Canadian Coast Guard, Fleet Safety Manual, Fourth Edition (September 2012). and the CCG Towing GuideFisheries and Oceans Canada, Canadian Coast Guard, CCG Towing Guide (March 2013). contain detailed towing guidelines for CCG masters. For example, a rough estimate of the maximum hull speed of the vessel intended to be towed can be calculated based on its waterline length. The closer the towing speed is to the hull speed (effectively the maximum speed), the more forces are exerted on the towline and the vessel. As well, the vessel’s master should be consulted.

According to the CCG calculation, the maximum hull speed of the Mucktown Girl was 9 knots. In this occurrence, based on a discussion between the masters and the Jean Goodwill master’s knowledge of the Mucktown Girl’s vessel type, a maximum hull speed of 10 knots was identified. At 10 knots, towing the vessel to Mulgrave, the intended destination, would have required about 9.5 hours.At the speed of the previous successful tow, 6 knots, the time required for this distance would have been closer to 16 hours.

Contingency plans are mentioned in both the CCG’s Fleet Safety Manual and the Towing Guide. The Fleet Safety Manual procedure 7.C.4, Towing Operations, requires that each CCG vessel develop a ship-specific procedure for towing other vessels that considers the capabilities and limitations of the vessel and crew. The ship-specific procedure for the Jean Goodwill was in the form of a checklist and emphasized communication between the vessels and procedures for disconnecting the towed vessel (see Appendix C).

The Towing Guide requires a contingency plan to be developed for scenarios that may occur while the vessel is engaged in towing. This information should be communicated to personnel on both vessels. Key considerations in the development of an operation-specific contingency plan include the following:

- Parting of the Towline. Plan should address the retrieval and reconnection of the towline as well as any alternative equipment and techniques that may be used in open water and ice.

- Sinking or capsizing. Plan should address action to be taken by either vessel in the event one vessel capsizes and/or sinks with the towline connected.

[…]

- Heavy weather in open water and/or when ice is present.Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Canadian Coast Guard, CCG Towing Guide (March 2013), section 2.1: Plans.

1.10.5 Guidance for removing crew members from a vessel

Transferring people between vessels at sea is inherently risky. To evaluate the risks of taking some or all crew members off a vessel, a CCG master follows a consultation process similar to the process for towing vessels and assesses factors such as the following before offering to remove some or all crew members from a vessel:

- Whether sea state, wind, and weather conditions allow for a safe at-sea transfer

- The willingness of the master and crew of the ship to be removed from the vessel

- The distance to be towed

- The type and severity of the emergency on board

- The number of persons to be removed and the ability of the CCG vessel to accommodate them

- The danger from unmonitored equipment on a towed vessel during the towing operation (pumps, electrical systems, machinery, rudder shaft)

In practice, crew members are rarely removed from a vessel in tow and the CCG does not conduct drills for this scenario.

In this occurrence, the master of the Jean Goodwill and the master of the Mucktown Girl discussed the weather, the tow, and the Mucktown Girl’s master’s desire for the fastest speed possible, given the forecast. When the tow failed, they also discussed how to communicate while they were standing by overnight.

1.10.6 Training for towing and search and rescue

In addition to the basic level of marine emergency training and drills required for Canadian commercial vessels, the CCG provides specialized training for towing and for SAR.

As well as training on the material in the Fleet Safety Manual and the Towing Guide, CCG deck officers and crew may receive 5.5 hours of training in towing as part of the rigid hull inflatable operator training, of which 4 hours are practical exercises.Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Canadian Coast Guard, CCG Small Craft Training Program – Advanced/Rigid Hull Inflatable Operator Training (RHIOT) (Syllabus) (July 2017), p. 13. The person overboard practical exercise is done from the FRC with one person in the water. For the safety of participants, practical exercises are carried out in daylight, in good weather, and close to shore.

The standard is to always have 2 crew members with this training in each crew. On the occurrence voyage, 7 crew members on board had this training.

In 2019, the CCG began training all deck officers and crew via an introductory emergency towing course designed for participants with limited knowledge of towing and emergency towing.This 21-hour course covers emergency towing and towing equipment, arrangements, and operations. Deck officers also take a second level, simulation-based course. Both courses are delivered by Memorial University’s Marine Institute.Fisheries and Marine Institute of Memorial University of Newfoundland, Short Courses, at https://www.mi.mun.ca/shortcourses/ (last accessed 17 October 2024).

CCG officers receive training in SAR coordination and may receive advanced training in medical responses. Other skills are developed through training such as person overboard drills, on-board familiarization, and regional exercises. These regional exercises may be; tabletop exercises or full-scale, multi-vessel exercises involving air and shore assets. Formal training for CCG officers and crews is delivered by the Canadian Coast Guard College, and additional practical exercises are carried out on the smaller CCG vessels. The training curricula do not contain sections about vessel-specific adaptations such as might be required for the larger, multipurpose vessels.

Some of the Jean Goodwill’s crew and officers had participated in regional SAR exercises and 1 officer had attended the introductory emergency towing course. At the time of the occurrence, the Jean Goodwill had not participated in any regional SAR exercises or other towing exercises.

1.10.7 Canadian Coast Guard vessels and equipment

The CCG fleet includes training vessels, small SAR cutters (also called lifeboats), patrol vessels, multipurpose vessels, icebreakers, and channel survey vessels.

Most of the towing in the Atlantic region is done by the small SAR cutters, which are designed for SAR operations. These vessels are closer to the same size as the fishing vessels being towed and have a range of approximately 200 NM. For example, the Spindrift is of 15.8 m and 43 GT, with a low freeboard that makes rescue directly from the water possible. Even when a larger vessel starts to tow offshore, a small SAR cutter is likely to pick up the towed vessel closer to shore and complete the towing operation. The small SAR vessels are assigned primarily to SAR duty and so they respond to most calls for assistance.

Many larger vessels are assigned primarily to icebreaking or offshore patrol duty. Any vessel may respond to a SAR call, but the larger vessels do fewer rotations where they are on primary SAR duty.

The Jean Goodwill and the Captain Molly KoolA 3rd vessel of this design, the Vincent Massey, was also acquired in 2018 and entered service in September 2023. were built from the same design and entered service in 2021 and 2019 respectively. They were originally anchor-handling tug supply vessels with ice-breaking capabilities, often used for moving the vessels and rigs of the oil and gas industry. For efficient towing, they are fitted with powerful winches that can be controlled remotely from the wheelhouse, and they have a long, low, open aft deck that is frequently awash during heavy weather.

These vessels were converted to medium icebreakers when they were acquired. On the Captain Molly Kool, the towing winches were retained when it was converted to an icebreaker. On the Jean Goodwill, the towing winches were removed and towing operations are conducted manually from the aft deck instead of from the wheelhouse.

The medium icebreakers and other larger vessels are equipped with FRCs. According to the letter of compliance issued under the Small Vessel Compliance Program,The Small Vessel Compliance Program is a TC program designed to help owners and operators of small commercial vessels meet safety requirements. (Source: Transport Canada, Small Vessel Compliance Program, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/programs/small-vessel-compliance-program [last accessed 08 November 2024]). the Jean Goodwill’s FRC was restricted to operations in waves of up to 4 m and winds of up to 41 knots. Although at least 1 crew member was certified to operate FRCs after sunset and before sunrise, or in conditions of reduced visibility, the letter of compliance stated that the Jean Goodwill’s FRC was restricted from operating in these conditions.

As part of the CCG SMS,Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Canadian Coast Guard, Fleet Safety Manual: 7.D.1 – Search and Rescue Operations, Fourth Edition (September 2012). the CCG has requirements for the vessels it operates, and the Jean Goodwill was required to have 2 scramble nets. At the time of the occurrence, the requirements for the type of scramble nets had just been changed to conform to International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) standards but the scramble net on board the Jean Goodwill had not yet been replaced.

At the time of the occurrence, some of the other larger CCG vessels were equipped with rescue scoops, such as the Capt Jacques Cartier, the John Cabot, and 2 vessels in the Pacific region.

1.11 Search and rescue preparedness

Real value in preparedness can be developed through exercises and well-developed follow-up evaluation of the exercises. Interacting with various entities involved in SAR allows resources to practise and evaluate leadership and team performance in a variety of SAR contexts. Realistic scenarios are those with a focus on survivor extraction techniques, leadership communication, risk assessment techniques, decision-making aids, and contingency planning. Theoretical tabletop exercises combined with live exercises are critical forms of practice that fuel SAR preparedness. At the tactical on-scene level, exposure to quickly evolving scenarios supports the practice in “[…] incident command skills with respect to the five categories of situational awareness, decision making, teamwork, leadership and communication.”J. Schmied, O. Borch, E. Roud et al., “Maritime Operations and Emergency Preparedness in the Arctic–Competence Standards for Search and Rescue Operations Contingencies in Polar Waters,” in The Interconnected Arctic – Arctic Congress 2016 (Springer, Cham, June 2017), pp. 245–255.

1.12 Decision making in emergencies

Situational awareness and performance biases are factors that can affect decision making and effectiveness in an emergency.

As emergency situations grow more complex, the volume of data that must be processed as part of decision making increases. In dynamic scenarios such as emergency situations where conditions and factors are quickly evolving, expert decision makers recognize situations as typical and familiar and proceed to take action (naturalistic decision making).G. Klein, Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions (MIT Press, 1998), pp. 24–30. They understand what types of goals make sense, what priorities to set, which cues are important, and what to expect next, as well as typical ways to respond in given situations. By recognizing situations as typical, they also recognize a course of action likely to succeed. This strategy of decision making is extremely efficient and is performed very quickly. A good situation assessment is critical to good decision making.

When the towing arrangement broke, the situation changed. There was no other safe way to tow, so the goal became to stand by and wait to reestablish the tow. The critical cues included the broken bollard, available material, and deteriorating weather.

1.12.1 Situational awareness

People working in operational environments make decisions by building a mental model of their operational environment. This mental model is supported by their situational awareness, which is developed through “the perception of elements in the environment within a volume of time and space, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status in the near future.”M. Endsley, “Toward a Theory of Situation Awareness in Dynamic Systems,” in Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, Vol. 37, Issue 1 (1995), p. 36.

Situational awareness is a critical component of decision making. However, any shortcomings during perception, comprehension, or projection of the future status of elements of a situation may result in an incomplete or inadequate situational awareness. A person’s knowledge, experience, training, and fitness for duty can also influence situational awareness.

A master is constantly perceiving various elements as a voyage unfolds, developing an understanding of their meaning, and predicting the effects these elements will have on the outcome of the voyage. Situational awareness is driven not only by the data available to the master, but also by the goals, environment, procedures, experience, knowledge, and availability of time.

1.12.2 Plan continuation bias

Plan continuation may result in a person attempting to resolve an abnormal situation or emergency by adhering to a chosen course of action despite indications that an alternative approach is required. The bias is shaped by the context in which the person works, the resources available, and their operational goals.

The bias can be set and encouraged by the initial presence of strong and persuasive cues that are perceived to support the chosen course of action. The effect of the bias is not easily recognizable, in part because abnormal events surrounding an emergency can develop slowly and ambiguously. The bias can result in the person believing that actions taken to address an emergency are effective and the situation is under control, even in the presence of cues suggesting that it is not. Human factors research has indicated that “[e]ven more important than the cognitive processes involved in decision making, are the contextual factors that surround people at the time.”S. Dekker, The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error, 3rd Edition (Ashgate Publishing, 2014), p. 94.

Ambiguous cues indicating that alternative actions should be taken may not be compelling to the person at the centre of an emergency. As time progresses in a complex environment, other critical tasks are added to the person’s cognitive workload, which may reduce their capacity to detect important cues that the current plan is ineffective or risky. The narrowing of attention in a stressful situation may support plan continuation, because a high workload and time pressures are not conducive to pausing to consider alternatives.

1.13 Risk perception and risk tolerance

Risk is a combination of the frequency or likelihood of a hazardous event and the severity of the consequences.International Maritime Organization, MSC-MEPC.2/Circ.12/Rev.2, Revised Guidelines For Formal Safety Assessment (FSA) For Use In The IMO Rule-Making Process (09 April 2018). Risk can be defined in terms of 2 separate constructs: perception and tolerance. Risk perception is a person’s recognition or discernment of risks inherent to a situation: a high level of risk for one person may be perceived as only low risk for another. Risk tolerance is the amount of risk that an individual is willing to accept in a pursuit of an objective.M. Martinussen, D.R. Hunter, Aviation Psychology and Human Factors, 2nd Edition (Taylor & Francis Group, 2018), pp 297–301.

What risks are perceived and what level of risk is tolerated are largely subjective. The TSB’s 2012 report on the safety issues investigation into fishing safety in CanadaTSB Marine Investigation Report M09Z0001, Safety Issues Investigation into Fishing Safety in Canada. showed that fish harvesters tend to have a high tolerance for risk.

1.14 Post-occurrence drug and alcohol testing

The use of drugs and alcohol on board fishing vessels has been identified as a growing concern by members of the fishing industry.Marine transportation safety investigation reports M21C0214, M21A0065, and M19A0090. Impairment from alcohol or drugs involving individuals in safety-critical positions can have significant adverse outcomes, affecting the safety of vessels, crews, and the environment. In this occurrence, the use of drugs and alcohol was reported on the Mucktown Girl before and during the voyage.

Current Canadian law does not require systematic drug and alcohol testing following a marine accident or incident. Without systematic testing, accident investigators must rely on eyewitness reports of drug and alcohol use, which, if available, provide limited information.

1.15 Voyage data recorder

The purpose of a voyage data recorder (VDR) is to record and safeguard critical information and parameters relating to a voyage. VDR data is invaluable to investigators when they attempt to understand a sequence of events and identify operational problems and human factors issues. If the VDR has a save button, the button must be activated following an occurrence for the data to be retrievable. If the VDR records continously for a rolling period, the data must be retrieved within that period.

At the time of the occurrence, the Jean Goodwill had a VDR on board that continuously recorded for a 30-day period. Not all of the bridge team members were aware that the vessel was fitted with a VDR and, as a result, the occurrence data was overwritten because it had not been saved. Therefore, the VDR data was not available to the TSB.

The TSB has investigated a number of occurrences in which the absence of VDR data limited the information available for the investigation.TSB marine transportation safety investigation reports M20C0145, M19C0403, M19P0057, M17P0400, M15C0094, M14C0193, M11L0160, and M11C0001.

1.16 Previous occurrences

It is common for vessels to request to be towed. Complications from a failed towing operation are relatively rare but can have serious consequences. The TSB has previously investigated the following occurrences involving failed towing operations:Data on all marine transportation occurrences reported to the TSB is available at www.tsb.gc.ca/eng/stats/marine/data-6.html. It is updated monthly.

- M14A0014 (John I) – On 14 March 2014, the bulk carrier John I became disabled off the southwest coast of Newfoundland and Labrador due to flooding in the engine room. The vessel called for a commercial tow. On the following day, a CCG vessel arrived. A tow was accepted after approximately 3 hours as the weather worsened, but the 2 vessels were unable to establish a towing arrangement. Shortly afterwards, the John I grounded on the Rose Blanche Shoals. There were no injuries, and all 23 crew members were evacuated by helicopter.

- M13N0001 (Charlene Hunt) – On 24 January 2013, the United States (U.S.)–flagged tug Charlene Hunt lost its tow off Cape Race, Newfoundland and Labrador, when the towing arrangement failed in heavy weather. The lost vessel, the decommissioned passenger vessel Lyubov Orlova, drifted in international waters and is presumed sunk.

M08M0010 (L’Acadien II) – On the morning of 29 March 2008, the small fishing vessel L’Acadien II, with 6 crew members on board, capsized 18 NM off Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, while being towed in ice by the light icebreaker CCGS Sir William Alexander. Two crew members were quickly rescued by another small fishing vessel. Several hours later, the bodies of 3 crew members were recovered from the overturned vessel by Canadian Armed Forces SAR technicians. One crew member was not recovered and was subsequently declared dead.

Following this occurrence, the TSB recommended that the Department of Fisheries and Oceans develop comprehensive safe towing policies, procedures, and practices that take into account all safety risks associated with towing small vessels in ice-infested waters. In response, the CCG added to its procedures criteria for removing crew when towing in ice.

Difficult towing operations occur worldwide. The following occurrences provide examples:

On 15 February 2016, in developing gale conditions, the fishing vessel Capt. David became disabled and began flooding about 40 miles off Oregon Inlet, North Carolina, U.S., while attempting to assist another disabled fishing vessel. A U.S. Coast Guard vessel was dispatched and a U.S. Navy vessel, USS Carter Hall, which was operating nearby, also provided assistance. At the urging of the Navy crew, the crew of the Capt. David abandoned their vessel into the Navy boat. The Capt. David later sank. The crew of the other disabled fishing vessel declined rescue, and the vessel was towed back to Oregon Inlet by the U.S. Coast Guard motor lifeboat several hours later. No injuries or pollution were reported.U.S. National Transportation Safety Board, Marine Accident Brief DCA16PM026, Flooding and Sinking of Fishing Vessel Capt. David (05 April 2017), p. 1, at https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/MAB1712.pdf (last accessed on 18 October 2024)

In its report, the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board stated that mariners should consider that an emergency during conditions of increasing winds and sea states risks endangering the crew and the rescue response personnel. The report also stated that it is prudent to carry a towline suited for the size and displacement of the vessel.Ibid, p. 13.

On 15 December 2012, the Vos Sailor was on station off the Balmoral Platform in the North Sea. The vessel was struck head-on by a large wave that shattered navigating bridge windows and dislodged the protective shutters that were in place. The chief officer died and another crew member was injured. One member of the rescue team was injured during the response. The damage that was sustained from the impact rendered both the vessel’s navigation systems and propulsion controls ineffective, removing the capability to summon assistance or proceed to a place of refuge. The anchor-handling vessel Stril Commander was nearby but was unable to connect a tow due to the bad weather. The tow was eventually picked up by MV Kestrel and the vessel was towed to Fraserburgh Harbour, Scotland, on the evening of 16 December.The Bahamas Maritime Authority, Report of the investigation into storm damage to “VOS SAILOR” whilst on dodging manoeuvres near the Balmoral Platform in the North Sea, 15th December 2012 (02 August 2013), p. 4, at https://www.bahamasmaritime.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/BMA-Investigation-Report-Heavy-weather-damage-to-the-VOS-Sailor.pdf (last accessed 04 December 2023).

In its report, the Bahamas Maritime Authority praised the level of emergency preparedness and emphasized the importance of emergency drills that incorporate unexpected factors into the process.Ibid., pp. 9 and 11.

1.17 TSB Watchlist

The TSB Watchlist identifies the key safety issues that need to be addressed to make Canada’s transportation system even safer.

Commercial fishing safety is a Watchlist 2022 issue. The Board placed commercial fishing safety on the Watchlist in 2010. Every year, the same safety deficiencies and unsafe work practices on board fishing vessels continue to put at risk the lives of thousands of Canadian fish harvesters and the livelihoods of their families and communities. From 2018 to 2020, there were 45 fish harvester fatalities, which is the highest fatality count for a 3-year period in over 20 years. Fishing vessels make up a large proportion of vessels towed by the CCG in the Atlantic region. This occurrence involving the Mucktown Girl demonstrates the risks to both fish harvesters and rescuers even when resources are available for help.

ACTION REQUIRED The issue of commercial fishing safety will remain on the Watchlist until there are sufficient indications that a sound safety culture has taken root throughout the industry and in fishing communities across the country, namely:

|

2.0 Analysis

The analysis focuses on events that occurred after the Mucktown Girl called for assistance, including the decisions made in planning the towing operation, the events after the towing arrangement failed, and the preparedness of the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) crew for the rescue operation. As well, the guidance for towing operations related to the towed vessel was examined.

2.1 Decision to tow with crew on board

The CCG in Atlantic Canada routinely receives requests for assistance from disabled vessels as well as from vessels in distress, in part because commercial towing is rarely available in this region. However, the master of a CCG vessel that is dispatched to provide assistance to such a vessel makes the final decision about how to assist, for example by providing support while repairs are made or by towing the vessel to port. In practice, towing is the most common response. The final plan for towing is agreed upon by the masters of the CCG vessel and the disabled vessel.

Typically, masters of disabled fishing vessels want to remain on board unless they perceive a serious risk. As well, transferring people between vessels at sea is inherently hazardous. Therefore, a CCG vessel typically tows a disabled vessel to shore with the crew on board, although the masters of the 2 vessels may discuss removal of the crew if the vessel is damaged or there is another reason to remove them. Except when a vessel is being towed in the presence of ice, when CCG guidelines specify that the crew must be removed from a vessel being towed, decisions around when to remove crew from a disabled vessel are left to the discretion of the masters of both vessels.

In this occurrence, the master of the Mucktown Girl requested a tow and reported that there was no damage or other problems on the fishing vessel except that it had no power. Because there was no damage to the vessel, it was initially assessed as disabled, not in distress or imminent distress, and therefore neither Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (JRCC) staff nor the master of the Jean Goodwill suggested removing some or all the crew of the Mucktown Girl, who all remained on the vessel. However, the Jean Goodwill had no means to remove crew from the disabled vessel after weather conditions had deteriorated well beyond the specified operating limits of its fast rescue craft (FRC).

2.1.1 Towing speed

On the voyage to the Mucktown Girl, the master of the Jean Goodwill reviewed the tow of the Mucktown Girl from 5 weeks earlier, the CCG risk register, and the weather forecast. The master also communicated a few times with the master of the Mucktown Girl to get the most up-to-date information about the condition of the vessel and the crew. When the Jean Goodwill arrived on scene, just after 0900, the condition of the Mucktown Girl was assessed. Since the Mucktown Girl did not have power, the Jean Goodwill dispatched its FRC to supply a set of VHF radios and spare batteries to the Mucktown Girl so that communications could be maintained.

The vessels were approximately 72 nautical miles (NM) from Canso, Nova Scotia, which is at the entrance to the more protected waters of Chedabucto Bay and another 23 NM from Mulgrave, Nova Scotia, their intended destination. The average speed of the previous successful towing operation between the Jean Goodwill and the Mucktown Girl was 6 knots. However, winds were forecast to increase to 35 to 40 knots well before the vessels would reach shelter, i.e., for the 2nd half of the towing operation the vessels were likely to be exposed to gale force winds increasing to storm force with the associated wave heights. Consequently, the masters of both vessels agreed that it was urgent to reach Chedabucto Bay before the storm was forecast to peak and therefore an increased towing speed was required.

The initial towing speed of 9 knots was decided on by the master of the Jean Goodwill in consultation with the master of the Mucktown Girl; a speed of 9 knots was very close to the Mucktown Girl’s hull speed, which is effectively a maximum speed for a vessel. However, as the speed increases, the forces acting on all parts of the towing arrangement also increase. As a result, the speed was reduced to 8 knots after less than 1 hour due to movement (yaw) of the towed vessel. At a speed of 8 knots, it would take approximately 9 hours to reach the more protected waters of Chedabucto Bay.

In this occurrence, the decision to tow in the forecast conditions and at the speed of 8 knots was likely influenced by the fact that towing is the most usual response to a disabled fishing vessel (an example of naturalistic decision making). Furthermore, this decision was likely influenced by the recent successful tow of the Mucktown Girl, which was perceived by the master of the Jean Goodwill to be a similar situation for which a similar response was suitable. Additional factors affecting decision making were the pressure to protect property (such as the fishing vessel), the assumption that the Mucktown Girl crew would not leave their vessel, and the knowledge that no other vessel in the area had responded to the JRCC’s maritime assistance request broadcast (MARB)A. Also, likely for these reasons, alternative options such as waiting out the storm or removing some or all the crew from the disabled vessel were not factored into the official towing plan. Although the master of the Jean Goodwill mitigated the risk of the towline breaking under the difficult weather conditions by making the towline longer to provide more catenary, no contingency plans were made for a possible need to slow down further, possible changes in the condition of the towed vessel, the tow failing, or any other effects of the worsening weather on the towing operation. The towing operation was anticipated to succeed because the towing speed was chosen to beat the weather and the length of the towline was increased to protect against the increased forces. Combined, these factors led to the Jean Goodwill attempting to tow the Mucktown Girl to shore before the storm hit.

2.2 Tow failure

There are risks involved in any towing operation, because the forces acting on the vessels and towing equipment can be large and are dynamic. The relative size and power of the towing vessel, the catenary of the towline, and the towing speed impact these forces, as do the reactions of the 2 vessels to waves and wind. In this occurrence, the difference between vessel sizes was large, the towing speed was close to the Mucktown Girl’s hull speed, and the wind action and wave heights were increasing. Combined, these factors increased the forces acting on the Mucktown Girl andapproximately 6 hours after the towing operation began, the bollard on the Mucktown Girl broke and the tow failed.

Before engaging in a towing operation, an assessment of the vessels and the conditions is required. A plan for towing should define the weakest point in the towing arrangement to ensure that shock forces do not overcome the towing equipment or damage the towed vessel. A plan for towing also includes contingency plans for anticipated hazards such as heavy weather in open water or ice, and events such as a vessel taking on water or the towing arrangement breaking. Finally, a plan for towing should include contingency plans for reestablishing the tow with a new towing arrangement or for actions if a new towing arrangement is not feasible, such as how to remove some or all of the crew from the towed vessel.

In this occurrence, when the bollard on the Mucktown Girl broke, there was no viable alternative towing point for a new towing arrangement. The winds were east-southeast at 30 to 35 knots with 2.5 m waves, and the weather was forecast to worsen quickly; within 30 minutes, winds had reached 35 to 40 knots with 4 m waves. JRCC and the master of the Jean Goodwill discussed options for reestablishing a tow and decided that the Jean Goodwill would stand by and await a weather window to reattach the towline, although they did not have a plan for a new towing arrangement. Consequently, the crew of the Mucktown Girl remained on board the vessel to weather the storm, adrift without power and emergency equipment such as portable pumps in case of water ingress.

2.2.1 Crew evacuation

As the Jean Goodwill stood by, the bridge crew checked in regularly with the master of the Mucktown Girl. When the Mucktown Girl was within 24 NM of shore (about 12 hours at their rate of drift), JRCC and the master of the Jean Goodwill considered plans for contingencies for the first time. The crew of the Jean Goodwill recognized that conditions were very difficult for the FRC, well beyond its specified operating limits. Consequently, towing by a CCG vessel similar in size to the Mucktown Girl and evacuation by helicopter were discussed. However, weather conditions and the broken bollard on the Mucktown Girl meant that a smaller vessel would be of limited additional help. Furthermore, the winds were forecast to shift, so the risk of going aground would be lessened. As a consequence, evacuation by helicopter was not discussed further, and the master of the Jean Goodwill and JRCC concluded that the Jean Goodwill would continue to stand by and monitor the situation.

Strong and persuasive cues that the plan to stand by and continue to leave the crew of the Mucktown Girl on the vessel existed, including agreement from JRCC that this was the best course of action and continued reassurance from the master on the Mucktown Girl about the vessel’s and the crew’s status. These cues reinforced the belief that the plan remained feasible, and likely also reduced the perception of risk related to leaving the crew on board.

The Jean Goodwill continued to receive reassurances from the Mucktown Girl master about the vessel’s and the crew’s status until morning, although the Mucktown Girl was adrift in waves reaching heights of more than 10 m at times, more than twice its height. However, just a few minutes after the established check-in at 0558, the master of the Mucktown Girl reported that there was 1.5 feet of water on main deck aft. With a large amount of water on the deck and without power, the crew of the Mucktown Girl felt the vessel was sinking and donned their immersion suits to abandon the vessel. At this point, the Jean Goodwill was 3.5 NM away, about 20 to 25 minutes. Originally, the crew of the Mucktown Girl were planning to jump into the water with immersion suits on to swim to the Jean Goodwill. However, the master of the Jean Goodwill instructed them to prepare their life raft instead. A short time later, and without any further communications, the crew of the Mucktown Girl boarded the life raft. The Mucktown Girl sank by the stern approximately 5 hours after the crew had abandoned the vessel.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

Without advising the Jean Goodwill, and in very rough seas, the crew of the Mucktown Girl abandoned the vessel into the life raft.

2.3 Preparedness for search and rescue operations

A search and rescue (SAR) operation is inherently unpredictable given that a situation can change quickly. SAR preparedness can assist in reducing the risk to those requiring rescue as well as to the rescuers. Part of SAR preparedness for responders is having the necessary tools easily accessible and being proficient in their use.