Safety issue investigation (SII)

Occurrences in Quebec and Nunavut on runways undergoing construction that are reduced in width

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Executive summary

This safety issue investigation examines a series of 18 occurrences that took place at certain airports undergoing construction in Quebec and Nunavut between 2013 and 2018.

Further to the investigation of an occurrence that took place in June 2018 when runway rehabilitation work was being carried out at the Baie-Comeau Airport, Quebec, it was discovered that another 14 similar occurrences had taken place at other airports in Quebec and at an airport in Nunavut since 2013. A summary review of these occurrences revealed a particularity in the method used to carry out the construction: the width of the runway was reduced rather than the length. In all but 2 cases, aircraft had manoeuvred on the closed portion of the runway during takeoff or landing.

Considering this a matter of concern, the TSB issued Aviation Safety Advisory A18Q0094-D1-A1, addressed to Transport Canada Civil Aviation (TCCA), on 12 July 2018. However, when 2 more similar occurrences took place shortly after the advisory was released, the TSB launched this investigation to highlight any systemic underlying causes or contributing factors, and assess the risk they pose. Information obtained during this investigation determined that an additional occurrence had taken place in Quebec, at the Schefferville Airport in August 2015, but had not been reported.

The construction method most frequently used for runway rehabilitation in Canada and abroad consists of reducing the runway length rather than the width. A review of international standards and recommended practices and of Canada’s regulatory framework for construction revealed the absence of information on which method should be used for runway rehabilitation, and the absence of Canadian standards for airport construction. Neither International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) documents nor the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs) and related standards authorize or prohibit either method. The decision lies entirely with the airport operator.

Given that reducing the width of a runway does not require the runway to be closed completely, this method provides a decisive advantage for operators of airports that have operational requirements or specific economic pressures, which was the case for the 4 airports reviewed in this investigation. However, this uncommon method requires that appropriate precautions be taken to ensure the safety of flight operations.

This method of runway rehabilitation requires a new configuration for runway markings. Without specific construction-related standards at their disposal, airport operators complied with regulations relating to airports. It was clear from reviewing these regulations that the various requirements and cases are complex and some concepts not detailed enough. If the wording used in airport standards and regulations is complex and lends itself to several interpretations, these standards and regulations could lead to different measures and solutions that all appear to comply with the requirements, but in reality, may not reflect the regulator’s intention with respect to safety.

Furthermore, given the absence of standards related to the safety of operations during airport construction, including standards related to required visual aids, the visual aids used on the reduced-width runways reviewed in this investigation were insufficient for pilots to be able to clearly distinguish the closed portions. The runway markings used for construction at the airports under review were not clear, convincing, and consistent; consequently, the pilots were not able to distinguish the open portion of each runway and manoeuvred the aircraft on the closed portion, which, in some cases, resulted in damage to the aircraft.

If an airport operator plans to carry out construction activities at their airport, they must communicate the necessary information to pilots by having a NOTAM issued by NAV CANADA. However, information pertaining to airport construction, which is temporary and may be complex, can be difficult to communicate clearly and effectively in a NOTAM. Over the years, the way these notices are presented and how they are provided to flight crews have not only been called into question several times, but have also been considered to be contributing factors in a number of aviation occurrences.

The investigations into those occurrences highlighted certain deficiencies that make these notices inadequate and could hinder the communication of the information. In addition to being written entirely in capital letters and consisting primarily of abbreviations and acronyms, these notices are published in a text format only, which limits how clearly a pilot can visualize areas that are closed due to construction. Currently, NOTAMs in Canada cannot include graphics and only include text, the format and style of which can hinder the effective communication of information. Consequently, even though the pilots involved in the occurrences under review had all read the available NOTAMs related to the partial runway closures, their mental models were inaccurate and they were not able to identify which portions were closed.

Consequently, the TSB recommends that

NAV CANADA make available, in a timely manner, graphic depictions of closures and other significant changes related to aerodrome or runway operations to accompany the associated NOTAMs so that the information communicated on these hazards is more easily understood.

TSB Recommendation A21-01

Any airport operator planning to carry out construction activities at their airport without interrupting operations must also prepare a plan of construction operations (PCO) and have it approved by TCCA. The purpose of the plan is to demonstrate that the airport will comply with established operating standards for the duration of the construction period. The investigation revealed that PCOs were difficult to prepare given the absence of standards, recommended practices, guidelines, and any other type of information on the subject. The absence of standards for the preparation of PCOs is in addition to the absence of general standards on airport construction and to the complexity of regulations regarding runway markings to be used.

The evaluation of a PCO by TCCA staff is vital to the safety of operations at an airport during construction. However, TCCA inspectors do not have standards or recommended practices at their disposal to complete the task. Consequently, in the absence of standards, guidelines, and recommended practices, PCOs were approved using informal procedures, without assessing the risk that pilots might not be able to recognize or distinguish the closed portions of the runways, and without including control measures to mitigate this risk.

The implementation of standards, recommended practices, and guidelines pertaining to the safety of operations during airport construction could improve the quality of PCOs, as well as the management of the risks associated with these temporary conditions and the safety of flight operations in these conditions. Consequently, the TSB issued Aviation Safety Advisory A18Q0140-D1-A1 to TCCA to make the organization aware of the absence of such standards, recommended practices, and guidelines pertaining to the safety of operations at airports undergoing construction, and to encourage the implementation of corrective measures as soon as possible.

Although safety measures are an integral part of airport operations and flight operations, they did not prevent the occurrences under review. Yet, these safety measures are part of a regulatory framework that promotes a systemic culture of safety and risk management for both airport operators and TCCA. The introduction of safety management systems (SMS) changed how safety is managed, by establishing a systemic risk management framework that includes a safety oversight component that should allow for proactive and reactive risk management. The 4 airports under review each had an SMS, but these SMSs did not comply with regulatory requirements and were not effective, given that they did not prevent the occurrences from happening in the first place or prevent repeated similar occurrences from happening. These SMSs were not assessed by TCCA when they were put in place, and the airport operators did not benefit from TCCA feedback and follow-up.

TCCA adopted its own internal SMS, the Integrated Management System (IMS), to implement and manage the Transport Canada (TC) Aviation Safety Program. With respect to the occurrences under review, TCCA was required to take action, including evaluating and approving the PCOs for the planned construction. However, the investigation determined that the TCCA inspectors had not followed IMS processes. For instance, they had not conducted risk assessments.

Safety management and regulatory surveillance are TSB Watchlist 2020 issues. The TSB has repeatedly emphasized the benefits of an SMS that allows companies to manage risk effectively and make operations safer. Yet, implementing an effective SMS is only part of the issue. Proper regulatory surveillance is also needed.

However, TC is not always able to identify ineffective operator processes and take action in a timely manner. For that reason, safety management will remain on the TSB Watchlist until operators in the air transportation sector that do have an SMS demonstrate to TC that it is working—that hazards are being identified and effective risk-mitigation measures are being implemented.

Likewise, regulatory surveillance will remain on the TSB Watchlist until TC demonstrates, through assessments of surveillance activities in the air transportation sector, that the new surveillance procedures are identifying and rectifying non-compliances, and that TC is ensuring that an operator returns to compliance in a timely fashion and is able to manage the safety of its operations.

This investigation has highlighted these deficiencies regarding airport surveillance. Although the occurrences under review took place primarily in Quebec and Nunavut, the investigation determined that these deficiencies all resulted from systemic underlying causes or contributing factors that a national safety program should have identified. Inevitably, it begs the question as to whether the situation is the same in other TCCA regions. In light of this, the Board is concerned that if TCCA does not provide adequate surveillance of airports in Canada, the risk of an accident related to flight operations at airports increases, particularly when the airports are undergoing construction.

1.0 Introduction

1.1 What is a safety issue investigation?

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s (TSB) mandate is to advance safety in transportation. It conducts investigations into occurrences in order to determine their causes and contributing factors, identify safety deficiencies, and make recommendations designed to mitigate or eliminate such safety deficiencies.

When several occurrences take place presenting commonalities and happening under similar circumstances, this could be an indication of systemic underlying causes or contributing factors.

When that happens, if the TSB determines that a significant safety issue exists, it launches a safety issue investigation. According to the TSB Policy on Occurrence Classification,Footnote 1 this type of investigation, which corresponds to a class 1 occurrence, consists of a comprehensive study into a series of occurrences with common characteristics and which, over time, have formed a pattern linked to one or more risks.

1.2 Context

Every runway will need to be rehabilitated at some point. The construction method used most often in Canada and abroad consists of temporarily reducing the length of the runway by closing the ends and performing the work on one end at a time or on both ends at the same time.

Another method, which is not as common, consists of reducing the runway width, dividing the entire length of the runway and closing one side of the runway at a time. However, this method, which is used in Canada in particular, has led to a number of occurrences during landings and takeoffs on reduced-width runways in Quebec and Nunavut.

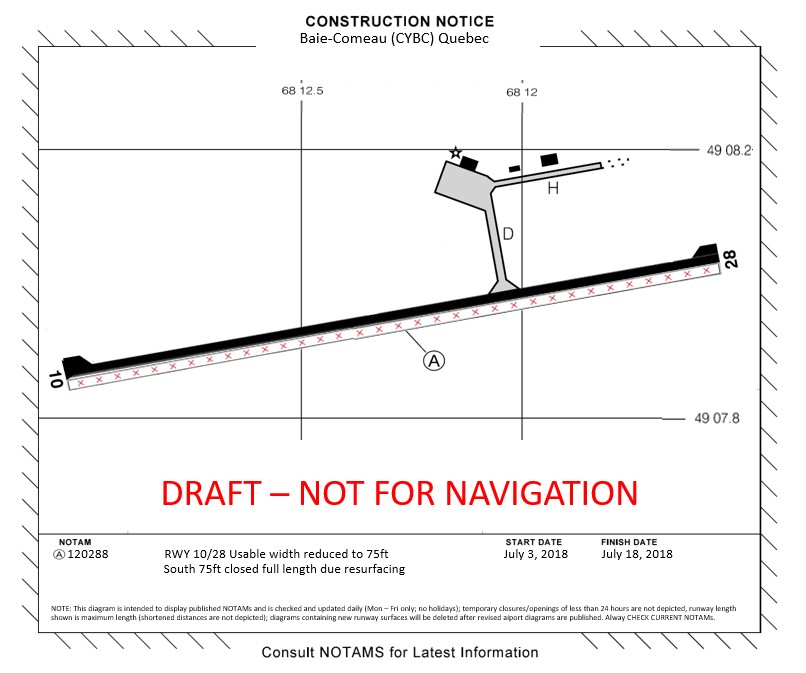

On 24 June 2018, a Bombardier DHC-8-300 aircraft operated by Jazz Aviation LP was conducting scheduled flight JZA8964 under instrument flight rules (IFR) from Mont-Joli Airport (CYYY), Quebec, to Baie-Comeau Airport (CYBC), Quebec, with 18 passengers and 3 crew members on board. Because of ongoing rehabilitation work being carried out on Runway 10/28 at the destination airport, the runway width had been reduced by half, to 75 feet, over the entire length of the runway, and only the northern lateral half was usable. As it was landing on Runway 10, the aircraft was lined up with the usual runway centreline—that is, the middle of the unreduced runway width—instead of the middle of the open lateral half of the runway. When the aircraft landed, the right main landing gear touched the ground on the closed lateral half of the runway. The gear’s inner wheel then struck a temporary runway edge light, causing a flat tire as the aircraft continued its landing roll toward the open lateral half of the runway. There were no injuries. Other than the flat tire, the aircraft was not damaged. The investigation determined that there were no closed markings on the closed southern lateral half of the runway.

This incident was reported to the TSB, which launched investigation A18Q0094. From the start of the investigation, a review of data from the TSB’s Aviation Safety Information System (ASIS),Footnote 2 Transport Canada Civil Aviation’s (TCCA) Civil Aviation Daily Occurrence Reporting System (CADORS)Footnote 3,Footnote 4 and NAV CANADA’s aviation occurrence report (AOR) systemFootnote 5 drew the TSB’s attention to the fact that this aviation occurrence was not unique. In fact, the compilation of the data available in these databases identified 15 occurrences that had taken place since 2013 involving a reduced-width runway at 2 airports in Quebec (Montréal/St-Hubert [CYHU] and Baie-Comeau) and at 1 airport in Nunavut (Iqaluit [CYFB]).

Given the high likelihood that more similar incidents could occur, and knowing that a landing or takeoff conducted beyond the established limits of a runway could cause serious injuries to occupants and significant damage to aircraft, the TSB issued Aviation Safety Advisory A18Q0094-D1-A1Footnote 6 to TCCA on 12 July 2018. The advisory stated that although a NOTAMFootnote 7 had been issued in each occurrence to indicate the closure of portions of the runway, the pilots were not able to quickly distinguish the open portion of the runway from the closed portion of the runway. It was therefore reasonable to conclude that the runway markings used during the rehabilitation work had not been effective, to the point where flight crews mistakenly believed that the entire width of the runway was available.

This aviation safety advisory immediately drew the attention of the Regional Community Airports Coalition of Canada (RCAC),Footnote 8 which then invited the TSB to give a presentation on the subject to its members. The TSB gave this presentation on 20 November 2018, at which time it learned that the method of reducing the runway width for construction work had previously been used elsewhere in Canada and that airport operators had a wide range of knowledge about and mixed views on the matter. A request to TCCA confirmed that this method had only been used at the Peace River Airport (CYPE), Alberta. It should be noted that no occurrences were reported during construction work at that airport.

The TSB’s concerns were heightened when 2 new similar occurrencesFootnote 9 took place in Quebec in 2018, after the release of Aviation Safety Advisory A18Q0094-D1-A1.

Given the number of similar occurrences taking place and their repetition at all of the airports in Quebec and Nunavut where the width of the runway had been reduced for construction purposes, the TSB launched this safety issue investigation. Using the methodology described in Appendix A, the TSB sought to determine the factors that led to these occurrences, analyze the existing lines of defence, and identify what could have prevented these types of occurrence or what could prevent them in the future.

It should be noted that information obtained during the investigation revealed that an 18th occurrence had taken place in Quebec, at the Schefferville Airport (CYKL), and had not been reported.

1.3 Scope

This report is meant for the aviation sector in general, and for airport operators and Transport Canada (TC) in particular.

The focus of this investigation is occurrences reported to the TSB that took place between 2013 and 2018 at airports in Quebec and NunavutFootnote 10 on runways whose width was reduced for construction activities. The year 2013 marked the first time an occurrence was reported involving a runway that was reduced in width during construction work. The year 2018 was when this investigation began.

This investigation first examines the various relevant aspects and existing lines of defence for Canadian airport operations, followed by those for flight operations in Canada. The investigation then focuses on safety management and airport surveillance in Canada. This investigation also draws a parallel with the situation in Alaska, another place where runways have been reduced in width to carry out construction activities. Finally, the investigation analyzes the various factors that led up to the occurrences under review despite the existing lines of defence, to identify deficiencies.

2.0 Occurrences under review

After obtaining the dates of all construction work performed on runways at airports within the TSB’s Quebec Region since the beginning of 2006,Footnote 11 a search was performed in the TSB’s Aviation Safety Information System (ASIS) database. This search did not reveal any occurrences related to a reduced-length runway, but did identify 15 occurrences related to a reduced-width runway. A review of NAV CANADA’s aviation occurrence reports (AORs) identified 2 other occurrences related to a reduced-width runway. These 17 occurrences took place between 2013 and 2018 at 3 airports: Montréal/St-Hubert (CYHU) and Baie-Comeau (CYBC) in Quebec and Iqaluit (CYFB) in Nunavut. The investigation also discovered an 18th occurrence that had taken place at Schefferville (CYKL), Quebec, in 2015, but had never been reported. This safety issue investigation will focus on these 18 occurrences (Appendix B).

2.1 Occurrences to be reported to the TSB

The Transportation Safety Board RegulationsFootnote 12 state when it is mandatory to report an occurrence to the TSB. Furthermore, the TSB Policy on Occurrence Classification defines the various classes of occurrences to be reported on a mandatory or voluntary basis.

The 18 aviation occurrences reviewed in this investigation can be broken down as follows:

- 1 class 3 occurrence that needed to be reported;

- 11 class 5 occurrences that needed to be reported;

- 3 class 5 occurrences that did not need to be reported, but were considered significant enough to be entered voluntarily as class 5 occurrences in the TSB’s database;

- 2 occurrences that did not need to be reported and were not considered significant enough to be entered voluntarily in the TSB’s database;Footnote 13

- 1 unreported occurrence, discovered during the investigation, which was not classified because not enough information was available.

2.2 Data available and common characteristics

The amount of information available for the majority of the 18 occurrences under review was limited given that most of them had been classified as class 5 occurrences and a few of them were not recorded in the TSB database. Only the information for the class 3 occurrence was detailed. An analysis of the data available, as limited as it was, highlighted some common characteristics (Table 1) among the various occurrences.

| Category | Characteristic | Number of occurrences with the characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Occurrence reporting | Recorded in the TSB database | 15 |

| Recorded in NAV CANADA’s AOR system only | 2 | |

| Unreported/unrecorded | 1 | |

| Airport size | Small airport that offered a local, regional, or remote service | 15 |

| Large airport that served a national, provincial, or territorial capital | 3 | |

| Safety management system (SMS) and plan of construction operations (PCO) | Airport where an SMS was required and put in place | 18 |

| Airport with an approved PCO | 18 | |

| Notification to pilots | NOTAM | 18 |

| AIP Canada (ICAO) supplement | 2 | |

| Time of occurrence | Day | 15 |

| Night | 2 | |

| Unknown | 1 | |

| Phase of flight | Approach or landing | 15 |

| Takeoff | 2 | |

| Unknown | 1 | |

| Occurrence type | Runway excursion | 16 |

| Aircraft struck temporary runway edge lights | 9 | |

| Aircraft landed on a taxiway | 1 | |

| Aircraft damage and injuries to occupants | Aircraft damage | 6 |

| Injuries to occupants | 0 | |

| Unknown | 1 | |

| Aircraft registration | Canadian | 11 |

| U.S. | 6 | |

| Unknown | 1 | |

| Aircraft category | Small aircraft* | 5 |

| Medium private and business aircraft** | 6 | |

| Medium-lift jet | 3 | |

| Medium-lift turbo-prop aircraft (commercial aviation – transport category) | 2 | |

| Jumbo jet (commercial aviation – transport category) | 1 | |

| Unknown | 1 | |

| Operation/operator type | Canadian general aviation | 2 |

| Canadian private operator | 1 | |

| Foreign private operator | 3 | |

| Canadian commercial air services – aerial work | 2 | |

| Canadian commercial air services – airline operations | 6 | |

| Foreign commercial air services | 3 | |

| Unknown | 1 |

* Airplane that has a maximum permissible take-off weight of 5700 kg (12 566 pounds) or less.

** For the purposes of this investigation, medium private and business aircraft means a turbo-jet airplane that has a maximum weight of more than 5700 kg (12 566 pounds) and for which a Canadian type certificate has been issued authorizing the transport of not more than 19 passengers.

3.0 Airport operations in Canada

3.1 Context

This investigation focuses on occurrences that took place at airports. The Aeronautics ActFootnote 14 provides the following definitions:

aerodrome means any area of land, water (including the frozen surface thereof) or other supporting surface used, designed, prepared, equipped or set apart for use either in whole or in part for the arrival, departure, movement or servicing of aircraft and includes any buildings, installations and equipment situated thereon or associated therewith.

airport means an aerodrome in respect of which a Canadian aviation document[Footnote 15] is in force.Footnote 16

3.1.1 Background

Canadian airports and their operations have evolved over time. Transport Canada (TC) gives the following context in its Aviation Safety Program Manual for the Civil Aviation Directorate:

4. Until the 1990s, airports in Canada were owned, operated, or subsidized by the federal government through the Department of Transport. Beginning in 1992, control of many Canadian airports was devolved to local airport authorities. This governmental initiative would later become known as the National Airports Policy (NAP).

5. After conducting extensive studies in the early 1990's, the Government of Canada made the decision to commercialize a number of its major activities, including the operation of most airports and the provision of air navigation services. The transfer of airport operations began in 1992.Footnote 17

Today, TC still owns 41 airports:

- 18 small airportsFootnote 18 that offer local, regional or remote service and are operated by either TC (14) or a third party (4). Eleven of those 18 airports are in Quebec, 7 of which are operated by TC, specifically the Air, Marine, and Environmental Programs Directorate.

- 23 large airports that serve a national, provincial, or territorial capital, and are operated by third parties. These airports are part of the National Airports System,Footnote 19 which has a total of 26 airports. Three of these 23 large airports are in Quebec.

The occurrences under review in this investigation took place at 4 airports. The Schefferville Airport is one of the small airports owned by TC. It has a single runway and is critical to serving the community. It is operated by the Société aéroportuaire de Schefferville. The Montréal/St-Hubert and Baie-Comeau airports are privately owned and operated. The Montréal/St-Hubert Airport has 3 runways, 2 of which are parallel. The Baie-Comeau Airport has a single runway and is a hub for emergency medical evacuation flights. The Iqaluit Airport in Nunavut is part of the National Airports System. Like the Schefferville Airport, it has a single runway and is critical to serving the community. It is owned and operated by the territorial government.Footnote 20

3.1.2 Airport operator and airport manager

An airport operator is the holder of the airport certificate and may be a corporation (a company, a provincial, territorial, or municipal government, etc.) or a person.

If the operator is a corporation, airport management is delegated to a person: the airport manager.

The Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs) use the term principal to refer to this person, and defines it as follows:

a principal means:...

(h) in respect of an airport:

(i) any person who is employed or contracted by its operator on a full- or part-time basis as the airport manager, or any person who occupies an equivalent position,

(ii) any person who exercises control over the airport as an owner, and

(iii) the accountable executive appointed by its operator [...]Footnote 21

The terms manager and director are both used. Regardless of the title used, this person occupies an important position as the holder of the Canadian aviation document or on behalf of the holder. Contrary to similar positions with air operators and approved maintenance organizations, the airport manager position does not have any minimum requirements in terms of relevant experience or qualifications.

3.1.3 Airports Capital Assistance Program

Operating an airport requires significant resources that are at times beyond the means of the airport certificate holder. This is often the case for regional airports, which “can struggle to raise enough revenue for operations”Footnote 22 and their maintenance. However, these airports “play an essential role in Canada’s air transportation sector”Footnote 23 and they are essential to the communities they serve as they are often the only existing transportation link. That is why, in 1995, the federal government introduced the Airports Capital Assistance Program (ACAP), which provides support to eligible airports that “are not owned or operated by the Government of Canada.”Footnote 24 This program, administered by the Air, Marine, and Environmental Programs Directorate, provides funding for “airside safety-related capital projects”Footnote 25 that:

- improve regional airport safety;

- protect airport assets (such as equipment and runways);

- reduce operating costs.Footnote 26

In order to be eligible for ACAP, an airport must meet specific criteria,Footnote 27 such as demonstrating on its application that it offers year-round scheduled commercial passenger service.

Among the airports where the occurrences under review took place, the Montréal/St-Hubert and Baie-Comeau airports were eligible for ACAP and had obtained funding for the planned runway rehabilitation.

3.2 Standards and regulatory framework

Airport operations in Canada are governed by a variety of texts: act, regulations, policies, standards and recommended practices. Consequently, construction activities carried out at airports are subject to regulatory requirements and standards that airport managers must follow.

3.2.1 International standards and recommended practices

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a specialized agency of the United Nations, was created in 1944 to establish safety and security standards for civil aviation operations throughout the world. It publishes standards and recommended practices in 19 annexes to the Convention on International Civil Aviation.

Standard: Any specification for physical characteristics, configuration, matériel, performance, personnel or procedure, the uniform application of which is recognized as necessary for the safety or regularity of international air navigation and to which Contracting States will conform in accordance with the Convention; in the event of impossibility of compliance, notification to the Council is compulsory under Article 38.

Recommended practice: Any specification for physical characteristics, configuration, matériel, performance, personnel or procedure, the uniform application of which is recognized as desirable in the interest of safety, regularity or efficiency of international air navigation, and to which Contracting States will endeavour to conform in accordance with the Convention.Footnote 28

When a Contracting State does not comply, in whole or in part, with a standard contained in an annex, it must give notification to ICAO of all national differences.Footnote 29 Furthermore, the State is invited to extend such notification to any differences from the recommended practices contained in an annex when the notification of such differences is important for the safety of air navigation.Footnote 30

As an ICAO Contracting State, Canada agrees to comply, where possible, with the Organization’s standards and recommended practices.

ICAO’s Annex 14 discusses aerodromes in general and Volume I pertains to aerodrome design and operations. However, it makes no mention of any methods to be used for runway rehabilitation. Chapter 10 covers aerodrome maintenance, but it provides technical information and very little on airport operations during construction activities. At the time of this investigation, Canada had reported 113 differences from ICAO’s standards and recommended practices described in Annex 14, Volume 1. Of these 113 differences, 7 related to Chapter 10, but none of them concerned runway rehabilitation. All of the differences notified by Canada are published in NAV CANADA’s AIP Canada (ICAO).Footnote 31

In addition to its annexes, ICAO publishes a number of other documents, some of which clarify how to apply the standards and recommended practices found in the annexes.

Such is the case for the Aerodrome Design Manual, particularly Part 1, which discusses runways and is closely linked to the specifications stated in Annex 14, Volume I. This manual “fulfills the requirement for guidance material on the geometric design of runways and associated aerodrome elements.”Footnote 32 It states the physical characteristics of runways, including minimum widths and factors to be taken into consideration to ensure the safety of operations under normal circumstances.Footnote 33 However, it does not discuss these characteristics during construction work or directly address runway maintenance or rehabilitation.

3.2.2 Canadian Aviation Regulations

Aerodrome operations in Canada are governed by CARs Part III. Subparts 301 and 302 contain the requirements that are of interest to this investigation.

Subpart 301 applies to aerodromes, but excludes airports, heliports and military aerodromes. Section 301.04 states requirements regarding the runway markers and markings to be used when a runway is partially or fully closed for more than 24 hours: regardless of the runway length, a closed marking shall be displayed at each end of the runway or part thereof. This section also states that the markings do not apply when the closure is “for 24 hours or less.”Footnote 34

CARs Subpart 302 applies to airports and is therefore directly relevant to this investigation. It covers requirements for the issuance of an airport certificate and the obligations of airport operators, including the contents of an airport operations manual (AOM). According to certification requirements, the standards and recommended practices published for airports in Canada must be followed. The AOM is somewhat of a written contract between the airport operator and Transport Canada Civil Aviation (TCCA). It contains policies and procedures regarding airport operations. Airport operators must comply with their AOM if they wish to retain their operating certificate. Unlike CARs Subpart 301, Subpart 302 does not provide specific requirements regarding the runway markers and markings to be used when a runway is closed. Instead, it states that airport operators must comply with “standards set out in the aerodrome standards and recommended practices publications.”Footnote 35 (See sections 3.2.3.1 Procedures for the certification of aerodromes and 3.2.3.2 Aerodrome standards and recommended practices of this report.)

CARs Subpart 302 also includes the airport operators’ obligations to provide information when certain situations exist at airports, such as when construction work is being performed:

(2) Subject to subsection (3), the operator of an airport shall give to the Minister, and cause to be received at the appropriate air traffic control unit or flight service station, immediate notice of any of the following circumstances of which the operator has knowledge:

(a) any projection by an object through an obstacle limitation surface relating to the airport;

(b) the existence of any obstruction or hazardous condition affecting aviation safety at or in the vicinity of the airport;

(c) any reduction in the level of services at the airport that are set out in an aeronautical information publication;

(d) the closure of any part of the manoeuvring area of the airport; and

(e) any other conditions that could be hazardous to aviation safety at the airport and against which precautions are warranted.

(3) Where it is not feasible for an operator to cause notice of a circumstance referred to in subsection (2) to be received at the appropriate air traffic control unit or flight service station, the operator shall give immediate notice directly to the pilots who may be affected by that circumstance.Footnote 36

Finally, also within CARs Subpart 302, sections 302.500, 302.501 and 302.502 discuss safety management systems (SMS) that airport operators must establish and maintain pursuant to section 107.02 (see section 3.3 Safety management system of this report).

3.2.2.1 Exemptions from regulatory requirements

Subsection 5.9(2) of the Aeronautics Act allows the Minister of Transport or a designated representative to grant an exemption “if the exemption [...] is in the public interest and is not likely to adversely affect aviation safety.” Footnote 37 Furthermore, according to Staff Instruction (SI) REG-004, published by TCCA:

When considering a request for a ministerial exemption from the CARs, TCCA Headquarters and Regional personnel shall demonstrate due diligence and document the decision-making process. [...] Assessments shall be conducted for the consideration of all ministerial exemptions. An assessment is a comprehensive, documented process used in decision-making to determine a course of action. […]

The decision to issue, deny or cancel a ministerial exemption pursuant to subsection 5.9(2) of the Aeronautics Act shall be made further to an assessment(s) of the two following criteria:

(a)Aviation safety;

(b)Public interest.Footnote 38

3.2.3 Canadian procedures, standards and recommended practices

In addition to the CARs, there are standards and recommended practices that provide guidance for airport operations in Canada. These include Procedures for the Certification of Aerodromes as Airports (TP 7775) and Aerodrome Standards and Recommended Practices (TP 312),Footnote 39 which are incorporated by referenceFootnote 40 into the CARs and have the force of law.

3.2.3.1 Procedures for the certification of aerodromes

3.2.3.1.1 Applicability

The most recent edition of TP 7775 dates back to 1991. At that time, the Air Regulations and Air Navigation Orders were in effect, and under the leadership of the Director General, Air Navigation System, TCCA Civil Aviation Aerodrome StandardsFootnote 41 inspectors were using TP 7775 for their oversight activities. Since then, the CARs have replaced the former regulations and orders, but the 1991 version of TP 7775 has remained in effect and is still used by both airport operators and aerodrome inspectors.

3.2.3.1.2 Contents relevant to this investigation

As its name indicates, this publication describes procedures for the certification of aerodromes as airports, including the obligations of the airport certificate holder. With respect to construction at an airport, it states that if construction activities are planned at an airport, the holder of the airport certificate shall:

submit a Plan of Construction Operations to the Regional Manager, Air Navigation System Requirements, to obtain approval prior to carrying out any construction activities while continuing the operational use of runways, taxiways or other manoeuvring surfaces at the airport. All details of the construction activities, precautions, signage to be used, etc. are to be included in the plan.Footnote 42

However, no specifics are given regarding the method, nature, or extent of the activities; how the operator is to prepare the plan; or what process TCCA uses to evaluate and approve the plan.

With respect to the communication of information about construction activities, TP 7775 states that the airport operator must arrange for NOTAMs to be issued at least 10 days before the proposed restrictions come into effect.

3.2.3.2 Aerodrome standards and recommended practices

3.2.3.2.1 Applicability

The 5th and most recent edition of TP 312Footnote 43 came into effect on 15 September 2015. It should be noted that the 4 previous editions remain in effect, so the 5th edition does not supersede the 4th edition,Footnote 44 which dates back to 1993. Therefore, airport operators are not obliged to comply with the standards in the most recent edition. Section 302.07 of the CARs, commonly referred to as the “grandfather clause”, states that:

[t]he operator of an airport shall

(a)comply:

(i)subject to subparagraph (ii), with the standards set out in the aerodrome standards and recommended practices publications, as they read on the date on which the airport certificate was issued,

(ii)in respect of any part or facility of the airport that has been replaced or improved, with the standards set out in the aerodrome standards and recommended practices publications, as they read on the date on which the part or facility was returned to service, […]Footnote 45

In its Advisory Circular (AC) 302-18,Footnote 46 TCCA explains the CARs grandfather clause that allows an airport operator to continue complying with an edition of TP 312 other than the most recent one.

As a result, airport operators must keep a record of their facilities, indicating which edition(s) of TP 312 apply to each facility. For example, it is possible for an airport lighting system to have been certified in compliance with the 3rd or 4th edition, then further to an upgrade, the lighting system now complies with the 5th edition.

The occurrences under review in this investigation all took place on runways that needed to comply with the 4th edition of TP 312.Footnote 47 However, all information published with respect to level of service certification needed to comply with the 5th edition of TP 312.

3.2.3.2.2 Contents relevant to this investigation

TP 312 states the standards and recommended practices for airports in Canada. It establishes requirements such as the physical characteristics, obstacle limitation surfaces, visual aids, and technical services that operators of certified land aerodromes (i.e. airports) must satisfy in support of flight operations, with no mention of construction activities. The most recent edition presents an entirely new approach, and from now provides standards based on operations rather design. In AC 302-021,Footnote 48 TCCA explains that:

- (1)The introduction of TP312 5th edition is a change in the application concept of the “standards” affecting airport certification. This shift from the design based concept under the previous editions of TP312 to an operational concept in TP312 5th aligns the certification standards to the actual (or planned) operation at site by linking the standards to specific aircraft characteristics, aerodrome operating visibility condition, and level of service (Precision, Non-Precision, Non-Instrument)[...].

- (2)This change to an operational concept requires airport operators to be more knowledgeable of the aircraft operations occurring (or planned for) at the airport whereas previous editions of TP312 were of a design based concept using primarily the runway length in a Code number system to link the standards applicable to the facility.

(3) The operational based concept under TP312 5th edition uses specific characteristics of the critical aircraft (current or planned) to link the respective standards. Each standard in TP312 5th directs the reader as to which of these aircraft characteristics is being called upon by the standard. These characteristics include:

(a) Wingspan (with consideration of the aircraft approach speed category);

(b) Outer main gear span; and

(c) Tail height.

(4)With the introduction of TP 312 5th, all certified airport operators will be required to:

(a) amend their Airport Operations Manual (AOM) to include additional information; and

(b) submit an update to the aeronautical publications regarding the certification level of the various parts of the certified aerodrome (airport).

This is required so that aircrews may assess the aerodrome as being “...suitable for the intended operation” as currently required under 602.96 (2)(b) of the CAR. At this time, there is nothing in the Integrated Aeronautical Information Publications that informs the Aircraft Operator as to the certification level of the infrastructure provided at the airport. Only a general statement is provided as to whether or not the facility is “Certified” or “Registered”. This general statement does not provide the Aircraft Operator adequate detail as to the suitability of each facility offered at an airport.Footnote 49

The 4th and 5th editions of TP 312 both discuss the visual aids to be used to indicate closed or unserviceable portions of a runway.Footnote 50 Although the wording is different, both editions require closed markingsFootnote 51 at each end of a runway, or portion thereof, declared permanently closed or unserviceable. For temporary closures, the 4th edition recommends using these closed markings, but does not require them when the closure is for a “short duration” as long as sufficient notice is provided by air traffic services. The 5th edition also does not require closed markings when the closure is for a short duration if there are other means to advise pilots and vehicle operators of the closure. Neither the 4th nor 5th edition provides a definition for “short duration.” However, both editions provide the possibility of utilizing means or materials other than paint to indicate these short-duration closures when airport operators choose to display markings. The operators of the airports where the occurrences under review took place considered that a closure for a few weeks was a “short-duration closure,” which relieved them of the strict duty to display closed markings while the work was being performed.

In terms of other runway markings (runway edge markings, runway centreline markings, etc.), the 4th and 5th editions of TP 312 differ. The 4th edition states that these markings must be obliterated on the closed portion of the runway only when the closure is permanent. It should be noted that the French version of the 5th edition requires removal of these markings regardless of the duration of the closure, while the English version only requires removal of the markings in the event of permanent closure.Footnote 52

Finally, all runway markings applicable to normally open portions of runways, as described in TP 312, must be properly displayed on the open side of a reduced-width runway, in compliance with CARs Subpart 302,Footnote 53 the requirements of which are applicable at all times while a certificate is valid.

3.3 Safety management system

Historically, the safety of flight operations was strictly related to regulatory compliance and was based on reactive risk management in response to incidents and accidents. However, it became evident that regulatory requirements alone could not foresee all of the risks associated with a particular activity. It was then that the concept of SMS was introduced. An SMS consists of

[a] systematic approach to managing safety, including the necessary organizational structures, accountability, responsibilities, policies and procedures.Footnote 54

The SMS concept was quickly endorsed and recommended by ICAO. In 2005, TCCA required the implementation of SMS within civil aviation, initially for airlines and approved maintenance organizations.

In early 2008, SMSs became mandatory for airports pursuant to sections 107.01 and 107.02 of the CARs.

However, TCCA published 2 exemptions granting a delay in implementing SMS

to enable holders of airport certificates to introduce a safety management system in an orderly manner and without disruption of their normal operations, by following the SMS implementation program published by the Minister in the Advisory Circular 300-002 titled Safety Management System Implementation Procedures for Airport Operators.Footnote 55

According to these 2 exemptions, the Iqaluit Airport, as a member of the National Airports System, had until 31 March 2011 to implement its SMS and the Baie-Comeau, Montréal/St-Hubert, and Schefferville airports had until 31 March 2012.

According to the CARs, the holder of an airport certificate issued pursuant to section 302.03 of the CARs “shall establish, maintain and adhere to a safety management system.”Footnote 56 This system “shall be adapted to the size, nature and complexity of the operations, activities, hazards and risks associated with the operations of the holder”Footnote 57 and shall include:

(a) a safety policy on which the system is based;

(b) a process for setting goals for the improvement of aviation safety and for measuring the attainment of those goals;

(c) a process for identifying hazards to aviation safety and for evaluating and managing the associated risks;

(d) a process for ensuring that personnel are trained and competent to perform their duties;

(e) a process for the internal reporting and analyzing of hazards, incidents and accidents and for taking corrective actions to prevent their recurrence.Footnote 58

Furthermore, Subpart 302 of CARs stipulates that an airport’s SMS must include the following components:

(c) procedures for the collection of data relating to hazards, incidents and accidents;

(d) procedures for the exchange of information in respect of hazards, incidents and accidents among the operators of aircraft and the provider of air traffic services at the airport and the airport operator;

(e) procedures for analysing data obtained [...]Footnote 59

Subpart 302 of CARs further states that

[t]he person managing the safety management system shall:

(a) establish and maintain a reporting system to ensure the timely collection of information related to hazards, incidents and accidents that may adversely affect safety;

(b) identify hazards and carry out risk management analyses of those hazards;

(c) investigate, analyze and identify the cause or probable cause of all hazards, incidents and accidents identified under the safety management system;

(d) establish and maintain a safety data system, by either electronic or other means, to monitor and analyze trends in hazards, incidents and accidents;

(e) monitor and evaluate the results of corrective actions with respect to hazards, incidents and accidents;

(f) monitor the concerns of the civil aviation industry in respect of safety and their perceived effect on the holder of the airport certificate.Footnote 60

To help airport operators implement their SMS and meet CARs requirements, TCCA published Guidance on Safety Management Systems (SMS) Development,Footnote 61 in which SMS components are described in detail.

According to this guide, the safety oversight component of the SMS

is fundamental to the safety management process. Safety oversight provides the information required to make an informed judgment on the management of risk in your organization. Additionally, it provides a mechanism for an organization to critically review its existing operations, proposed operational changes and additions or replacements, for their safety significance. Safety oversight is achieved through two principal means:

(a) Reactive processes for managing occurrences, including event investigation and analysis;

(b) Proactive processes for managing hazards, including procedures for hazard identification, active monitoring techniques and safety risk profiling.Footnote 62

Figure 1 illustrates the safety oversight component of an SMS and highlights the 2 key aspects of safety management: the reactive aspect and the proactive aspect.

A proactive SMS “must actively seek out potential safety hazards and evaluate the associated risks.”Footnote 63 The airport operator must therefore consider the potential hazards of each activity. Risk assessments may be used to identify potential hazards and apply risk management techniques. These risk assessments should be undertaken “during the implementation of [the] SMS and at regular intervals thereafter” and “when major operational changes are planned.”Footnote 64 Therefore, a risk assessment should be carried out for runway rehabilitation that involves the partial closure of a runway given that this construction work is a major operational change.

If events occur despite proactive risk management, the SMS must allow the operator to react so that the events do not reoccur.

Every event is an opportunity to learn valuable safety lessons. The lessons will only be understood, however, if the occurrence is analyzed so that all employees, including management, understand not only what happened, but also why it happened. This involves looking beyond the event and investigating the contributing factors, the organizational and human factors within the organization, that played a role in the event.Footnote 65

The investigation revealed that only the Montréal/St-Hubert Airport had followed the proactive safety management process by conducting and documenting a risk assessment as part of its construction plan, and none of the airports had followed the reactive process required by CARs after the occurrences.

To prevent a potential issue in an SMS component from going undetected, and to ensure continuous improvement of the SMS, a quality assurance component was included.

According to the Guidance on Safety Management Systems (SMS) Development,

[a] quality assurance program (QAP) defines and establishes an organization‘s quality policy and objectives. It also allows an organization to document and implement the procedures needed to attain these goals. A properly implemented QAP ensures that procedures are carried out consistently, that problems can be identified and resolved, and that the organization can continuously review and improve its procedures, products and services.Footnote 66

Furthermore, TCCA explains in the guide that quality assurance is based on the principle of continuous improvement which, in most modern management systems, is achieved through the following steps: Plan, Do, Check, and Act (PDCA). A QAP corresponds to the Check step of the PDCA process and ensures that the Act portion achieves the desired results.

TCCA then stresses once again the importance of the process:

It has been said that “the emphasis with assuring quality must focus first on process because a stable, repeatable process is one in which quality can be an emergent property.” This emphasizes the importance of focusing on process and on the need to ensure that processes are documented. The reason we need to do this is that in order to verify the effectiveness of a process, it must be used; in order to improve a process, we must be assured that the process we are improving was in fact the process that was originally being used. Remember, you cannot improve a process unless that process has been documented. So, what is meant by process?

Process is the sequence of steps taken to arrive at a given output, and in the context used here, is the output from planning (Plan), it is the way that management expects work to be done.Footnote 67

The airport managers of some of the airports under review admitted to not properly understanding SMS requirements and not knowing whether or not the SMS they had implemented complied with regulatory requirements.

3.4 Runway rehabilitation

3.4.1 Plan of construction operations

Airport construction planning generally extends over several years. In Canada, from a regulatory standpoint, an airport operator cannot begin maintenance or improvement activities that will have an impact on certification without first submitting a plan to TCCA.

In accordance with TP 7775, if an airport operator plans to carry out runway rehabilitation without interrupting operations, the operator must prepare a plan of construction operations (PCO). Footnote 68 Given that the validity of an airport certificate depends on the AOM, once approved by TCCA, the PCO is like a temporary amendment to the AOM, describing the measures that will be put in place during construction to meet relevant standards and mitigate risks. Furthermore, because the operator has an SMS, it must follow the SMS’s principles and, if major changes are involved, perform a risk assessment.

Before preparing a PCO, airport operators must determine the nature of the construction activities required, the associated operational constraints, and in accordance with their SMS, they must identify potential hazards. According to airport operators, the elements that are generally considered and assessed are:

- the importance of the airport to the community it serves;

- the various flight operations that take place at the airport;

- the types of aircraft that use the airport;

- the number of runways;

- constraints related to the air operators that use the airport;

- seasonal conditions that dictate when the construction is carried out.

Given that there are no official standards or recommended practices for the preparation of PCOs, airport operators often ask consultants to draft their PCO. In general, the airport operator will authorize the consultant to prepare the PCO, a process that involves meetings and discussions with various stakeholders. If an applicable airport standard cannot be met during construction, the airport operator may request an exemption from TCCA. Once the PCO is ready, it is submitted to TCCA for evaluation and approval.

The TSB obtained a copy of the 39 PCOs approved by TCCA between 2006 and 2018 for the airports in Quebec and the Iqaluit Airport in Nunavut. Of the 39 PCOs, 4 were for the airports that had reduced the runway width and where the occurrences under review had taken place. A review of all the plans revealed that there was, indeed, no standard format for PCOs, and that they generally contained the following elements:

- description of the work to be performed;

- filing of plans;

- construction procedures;

- communications plan;

- closed portions of runways and temporary markings;

- on-site safety;

- appendices.

The review of the 39 PCOs also highlighted the fact that they included civil engineering information (paving techniques, logistics information on how to perform the work, plans, specifications, etc.). This information is neither reviewed nor validated by the inspectors tasked with approving PCOs. Although it is not related to any regulatory requirements, the possibility of obtaining financial assistance is also considered when a PCO is being prepared. In interviews conducted for the purposes of this investigation, airport operators explained that the civil engineering elements in the PCOs were related to funding requests submitted to the Air, Marine, and Environmental Programs Directorate under ACAP. In addition, the operators were under the impression that the least expensive option would be favoured by ACAP officers. For example, painting X on the surface of a freshly paved runway was not acceptable for ACAP given that the removal of these markers at the end of the construction work could damage the surface and lead to additional costs.

The addition of civil engineering information in the PCOs allowed airport operators to prepare a single document to demonstrate to the 2 TC entities—TCCA for approval of the work, and the Air, Marine, and Environmental Programs Directorate for funding—that their respective requirements were met, in addition to a common requirement where “applicants must show that their project is needed to meet the required level of safety.”Footnote 69

With regard to risk management in the PCOs reviewed, of the 4 airports where the occurrences under review took place, only 1 PCO included a risk assessment. The PCOs for the other 3 airports simply provided a reminder that airport operations were subject to the airport’s SMS and stated that SMS briefings or training would be given to stakeholders.Footnote 70

3.4.2 Construction methods

With construction work on a runway come traffic disruptions. Therefore, the goal of an airport operator that is planning construction is always to minimize these disruptions, and to minimize the time that the runway is closed completely.

3.4.2.1 Reduced-length runway

The construction method most often used in Canada and abroad consists of temporarily reducing the length of the runway by closing the ends and performing the work on one end at a time or on both ends at the same time. This way, the remaining portion of the runway can be kept open. Other benefits of this method are limiting the time that the runway is closed completely while work is performed on the middle part of the runway, and being able to keep the runway markings and lighting used in the normal runway configuration. This method is appropriate for small aircraft and certain types of larger aircraft that can operate on a reduced-length runway.

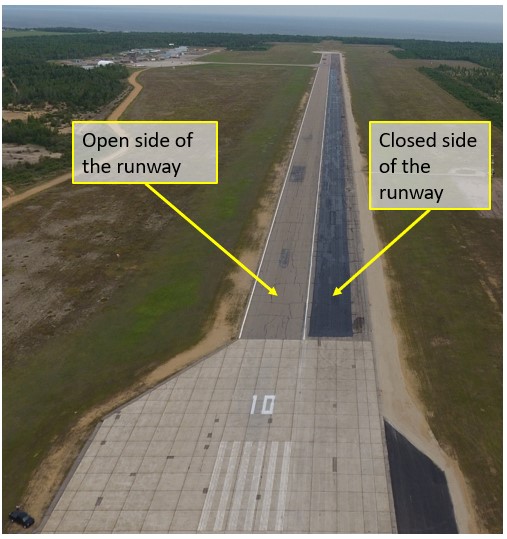

3.4.2.2 Reduced-width runway

Another method of runway rehabilitation consists of reducing the runway width—dividing the entire length of the runway in 2 and closing one side at a time while keeping the other side of the runway open. A benefit of this method is that it does not require complete closure of the runway; however, it does require a new configuration for runway markings and lighting. A reduced-width runway may be appropriate for small aircraft and for large aircraft, provided that they are approved for operations on narrow runways (see section 4.2.2 Narrow runway operations of this report). This is the method that was used in all of the occurrences under review.

Reducing the width of a runway for rehabilitation purposes does not seem to be common practice. The investigation determined that this method was rarely used in Canada and the United States (see section 6.0 Cases in the United States, and in Alaska in particular of this report).

3.4.2.3 Considerations when choosing a method

When choosing a method for runway rehabilitation, the airport operator must take several factors into consideration, including the role that the airport plays in the communities it serves. The airport operator must consult the affected communities to determine how to limit the disruptions caused by the construction work and the duration of the work. Small airports located in remote areas or far from large urban centres, and which often have only one runway, are indispensable to the communities they serve in terms of supplying essential products and emergency medical services. Because closing the one and only runway is not a viable option, regardless of the length of the construction period, the airport operator will choose to close a portion of the runway width.

The airport operator must also take economic factors into consideration when choosing the construction method. Even if an airport is relatively close to a large urban centre and has more than one runway, the airport operator cannot ignore the needs and requirements of air operators, who prefer that the runway be kept open, and therefore favour the runway rehabilitation method that involves closing a portion of the runway width.

Therefore, the operator of an airport that has passenger service provided by a single commercial air operator will choose the option that avoids closing the runway in order to have the least impact possible on the air operator’s operations.

3.4.3 Runway markings during construction

At aerodromes, visual aids are crucial to the proper use of taxiways, runways, and other movement areas, as well as to airside safety. Runways have various markings that enable pilots to properly identify the runway boundaries and centreline. When construction activities are carried out on a runway, some of the markings must be added, moved, or removed. When a runway or portion thereof is closed or unserviceable, closed markings (Figure 2) may or may not be required depending on the aerodrome’s status (certified or not), the duration of the closure, and in the case of airports (certified aerodromes), the edition of the standards and recommended practices (TP 312) that applies.

The occurrences under review in this investigation all took place on runways that needed to comply with the 4th Edition of TP 312.

Therefore, closed markings were mandatory for permanent closures, but only recommended for temporary closures; they could be omitted for short-duration closures. Furthermore, other runway markings (runway edge markings, centreline, etc.) did not need to be obscured in the closed area given that the closures were not permanent. Finally, the markings on the open side of the runway needed to comply with the standards stated in TP 312. The operators of the airports at which the occurrences under review took place had considered that a closure for a few weeks constituted a “short-duration closure,” which meant that they were not systematically required to display closed markings during the construction work.

An examination of the PCOs for the 4 airports under review revealed that the temporary runway markings varied greatly, not only between airports, but also between different phases of work at the same airport. Furthermore, the investigation determined that the markings that were actually in place at a given point in time did not always reflect what was planned and described in the PCO approved by TCCA. Owing to the temporary nature of the work and the scarcity of documentation available regarding the status of work while it was being completed, it was impossible to compile a list of all of the markings used that did not match the PCOs, whether or not they had been approved by TCCA after the initial approval of the PCO. The following sections provide examples of some of the differences in markings identified during the investigation at the airports under review for which photos were available, namely Iqaluit, Montréal/Saint-Hubert, and Baie-Comeau.

3.4.3.1 Iqaluit Airport

Construction at the Iqaluit Airport was to be completed over several phases, from May 2014 to December 2017, and was described in a single PCO. For the runwayFootnote 71 rehabilitation phases, a length reduction (displaced threshold) and a width reduction were planned. The PCO stated that the “runway closures” would be indicated by a temporary closed marking, without specifying whether the closures would affect the width, the length, or both. However, on the technical drawings that accompanied the description, closed markings were placed at regular intervals along the entire length of the closed side of the runway. The PCO did not specify whether the runway markings that no longer applied would be removed.

A Google Earth imageFootnote 72 of the Iqaluit Airport taken during construction (Figure 3) shows closed markings placed at regular intervals along the entire length of the closed side of the runway, and a new centreline was marked on the open side of the runway. However, the original threshold and centreline markings had not been removed and were still visible.

3.4.3.2 Montréal/St-Hubert Airport

Construction at the Montréal/St-Hubert Airport, which involved Runway 06L/24R,Footnote 73 was scheduled to take place over a period of 2 years and broken down into 6 phases: the 1st phase, which would take place in 2016, was described in one PCO, while phases 2 to 6, which would take place in 2017, were described in another PCO. Like the Iqaluit Airport, the construction work at this airport involved not only a reduction in the width of the runway, but also a reduction in the length (displaced threshold). During the 1st phase, the width of the runway would be reduced to 100 feet and the length would be reduced to 5000 feet. The temporary runway markings that were planned complied with TP 312. The PCO stated that, in order to clearly define the open portion of the runway, temporary runway edge markings would be placed on each side of the open portion of the runway. The PCO also indicated that closed markings (colour not specified) would be displayed at intervals of a maximum of 300 m over the full width of the closed runway (i.e. at both ends). It was also stated that illuminated X’s would be placed at both runway thresholds at night while the runway was closed completely.

The runway configuration for phases 2 to 6 also involved a reduction in the runway width (reduced to 75 feet) and length (displaced threshold), with the same arrangement of closed markings as that used in the 1st phase.

In reality, as shown in a photo taken by the TSB in 2016 during the 1st phase of construction (Figure 4), white closed markings with little contrast were installed in the grass on each side of the runway where it was closed along the entire width (displaced threshold).

3.4.3.3 Baie-Comeau Airport

Construction at the Baie-Comeau Airport was scheduled for June to August 2018 and was broken down into 7 phases, described in a single PCO. This PCO did not include a plan to display closed markings on the closed side of the runway,Footnote 74 but it did include a plan to place them in the grass for phase 5. The threshold markings and runway identification number would be removed from the closed side of the runway and the runway number would be displayed at the centreline of the open side. Finally, the PCO included a plan to replace the former runway centreline markings with runway edge markings and place runway centreline markings on the open side.

The planned runway edge markings were actually used; however, the centreline markings and closed markings were not (Figure 5). In light of the repeated incidents that were occurring during the rehabilitation of the south side of the runway, the airport operator decided to display a closed marking in the grass, on the closed side of the runway in line with each runway threshold, for the rehabilitation of the north side of the runway. These 2 markings were white, and larger than what was recommended in TP 312.

3.4.3.4 Peace River Airport

Construction at the Peace River Airport was scheduled to be completed in several phases during the summer of 2015, and was described in a single PCO. For the phases involving runway rehabilitation,Footnote 75 a reduction in the width of the runway was planned. The PCO stated that temporary centreline and threshold markings would be displayed on the open portion of the runway and would be removed before the final markings were put in place. Furthermore, technical drawings that accompanied the description showed closed markings at regular intervals on the runway strip, along the entire length of the closed side of the runway.

The investigation was unable to determine whether the proposed markings were applied as proposed.

3.5 Communication of construction information by the airport operator

Pursuant to paragraph 302.07(1)(d) of the CARs, an airport operator shall “notify the Minister in writing at least 14 days before any change to the airport, the airport facilities or the level of service at the airport that has been planned in advance and that is likely to affect the accuracy of the information contained in an aeronautical information publication.”Footnote 76 Furthermore, pursuant to subsections 302.07(2) and (3) of the CARs, an airport operator shall “give to the Minister, and cause to be received at the appropriate air traffic control (ATC) unit or flight service station, immediate notice”Footnote 77 of specific situations, including the closure of any part of the manoeuvring area at the airport.

To do this, the airport operator must communicate the required information to NAV CANADA, Canada’s exclusive provider of aeronautical information services. As part of its Integrated Aeronautical Information Package, NAV CANADA publishes the following aeronautical information products:Footnote 78 AIP Canada (ICAO), AIP Canada (ICAO) supplements, aeronautical information circulars (AIC), and NOTAMs. The nature and validity period of the information to be published determines the choice of product. In the case of temporary information, such as that pertaining to runway rehabilitation, 2 products are available: AIP Canada (ICAO) supplements and NOTAMs.

3.5.1 NOTAMs

Pursuant to TC’s TP 7775, an airport operator planning to carry out construction activities at its airport must issue a NOTAM before the work begins.

According to the Canadian NOTAM Procedures Manual,Footnote 79

[a] NOTAM is a notice distributed by means of telecommunications containing information concerning the establishment, conditions or change in any aeronautical facility, service, procedure or hazard, the timely knowledge of which is essential to personnel concerned with flight operations. [...]

The basic purpose of a NOTAM is the distribution of information that may affect safety and operations in advance of the event to which it relates, except in the case of unserviceable facilities or unavailability of services and activities that cannot be foreseen. Thus, to realize its purpose the addressee must receive a NOTAM in sufficient time to take any required action. The value of a NOTAM lies in its “news content” and its residual historical value is therefore minimal.Footnote 80

The process to request that a NOTAM be issued is quick and well known by airport operators, as they are regularly required to issue NOTAMs and have at their disposal the Canadian NOTAM Procedures Manual, which describes precisely how to prepare this type of message. When requesting that a NOTAM be issued, airport operators must provide the necessary information to the appropriate NAV CANADA flight information centre or flight service station.

NAV CANADA’s Canadian NOTAM Procedures Manual is based on ICAO standards in Annex 15,Footnote 81 in the Aeronautical Information Services ManualFootnote 82 and in the Procedures for Air Navigation Services – ICAO Abbreviations and Codes.Footnote 83

According to the Canadian NOTAM Procedures Manual, NOTAMs shall be

as brief as possible, stating only the essential facts,4 and so compiled that its meaning is clear and unambiguous. Clarity shall take precedence over conciseness.

4 NOTAMs are not issued after the fact just for the records to show that NOTAMs were issued. For example, if no NOTAMs were issued during the actual outage or closure, it is not permitted to promulgate the information after the fact.Footnote 84

The text is written entirely in capital letters and consists primarily of abbreviations and acronyms.Footnote 85 Also, NOTAMs do not contain graphics.

The versions of the manual in effect when the various occurrences under review took place indicated the following:

5 5.2.3.4 Runway Width Reduction

A NOTAM may be issued when a runway is closed along its length, thus reducing its width. If provided, the reason for the partial closure, such as resurfacing, and the restrictions if applicable, to aircraft size, shall be included.Footnote 86

Furthermore, the examples presented in the manual for a reduced-width runway included information on the affected runway, the closed portion along with its orientation (compass point), the width of the available portion and the wingspan of authorized aircraft. The various examples did not contain specific standard terms or acronyms to designate a reduction in runway width.

Example: 120001 NOTAMN CYUY ST-BRUNO-DE-GUIGUES

CTA4 SOUTH 50 FT RWY 10/28 FULL LEN CLSD DUE RESURFACING. ACFT WITH A WING SPAN GREATER THAN 50 FT NOT AUTH NORTH SIDE 50 FT

YYMMDDHHMM TIL YYMMDDHHMMFootnote 87

At the same time, the NOTAM examples given in the manual to illustrate a reduction in runway length contained acronyms pertaining to the distance available on takeoff or landing.Footnote 88 These acronyms are known by pilots since they are used in calculating aircraft performances.

Example: 170001 NOTAMN CYUL MONTREAL/PIERRE ELLIOTT TRUDEAU INTL

CYUL FIRST 1700 FT RWY 06R CLSD. THR 06R IS RELOCATED 1700 FT. DECLARED DIST:

RWY 06R TORA 7900 TODA 8884 ASDA 7900 LDA 7900

RWY 24L TORA 7900 TODA 7900 ASDA 7900 LDA 7900

YYMMDDHHMM TIL YYMMDDHHMMFootnote 89

At all of the airports under review, the NOTAMs issued for the various construction periods (Appendix C) followed the examples given in the various versions of the Canadian NOTAM Procedures Manual in effect when the occurrences under review took place.

3.5.2 AIP Canada (ICAO) supplements

Every ICAO Contracting State is required to publish an aeronautical information publication (AIP), which contains “aeronautical information of a lasting character essential to air navigation.”Footnote 90 Canada publishes the AIP Canada (ICAO), the main source for Canadian aeronautical information. It is updated regularly, and amendments are published every 56 days.

“[T]emporary operational changes of long duration (three months or longer), as well as information of short duration that contains extensive text and/or graphics, are published in an AIP Canada (ICAO) Supplement in accordance with the International Civil Aviation Organization’s (ICAO’s) Annex 15.”Footnote 91

AIP Canada (ICAO) supplements are published every 28 days. Airport operators who want to have an AIP Canada (ICAO) supplement published to disseminate information regarding airport construction must provide the information to NAV CANADA at least 49 days in advance. The investigation discovered that airport operators were often unaware of the process for requesting to have a supplement published for 2 main reasons: unlike NOTAMs, supplements are not documents that airport operators have published regularly, and the request process is not easy to find. It can be found in the Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM),Footnote 92 but it is not mentioned anywhere else, in any TCCA or NAV CANADA document or on any of their websites. The investigation determined that in order to have an AIP Canada (ICAO) supplement published, an airport operator had to submit a request by email or by telephone. Contact information is provided in the TC AIM.Footnote 93

Of the 4 airports where the occurrences under review took place, the Montréal/St-Hubert and Baie-Comeau airports had had an AIP Canada (ICAO) supplement published.

4.0 Flight operations in Canada

4.1 Types of flight operations

The occurrences under review fell under different categories of flight operations: general aviation (2 occurrences), private operators (4 occurrences) and commercial air services (11 occurrences). The category of one of the occurrences under review (Schefferville) is unknown.

General aviation primarily includes recreational pilots who use small single- or twin-engine aircraft for their personal needs. The pilots usually hold a pilot permit – recreational or a private pilot licence. They typically conduct relatively simple flights.

Private operators mainly include commercial pilots and turbo-prop or turbo-jet aircraft used for business or private needs. These pilots hold a private or commercial pilot licence and various additional ratings, as necessary. The aircraft used for this type of flight operations are higher performance and more complex than those used for general aviation. They often require 2 pilots. Pursuant to section 604.03 of the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs), their operation requires a private operator registration document, which is issued by Transport Canada Civil Aviation (TCCA) once the required criteria have been met. Footnote 94