Runway overrun

Keewatin Air LP

Beechcraft King Air B200, C-GBYN

Goose Bay Airport (CYYR), Newfoundland and Labrador

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

On 13 April 2024, at 0206 Atlantic Daylight Time, the Keewatin Air LP Beechcraft King Air B200 aircraft (registration C-GBYN, serial number BB 1232), departed Goose Bay Airport (CYYR), Newfoundland and Labrador, on an instrument flight rules medical evacuation flight to Québec/Jean Lesage International Airport (CYQB), Quebec, with 2 pilots, 2 medical staff, and 1 patient on board. Shortly after the departure from Runway 26, the flight crew received a left-engine fire indication. They requested a return to CYYR and subsequently declared an emergency. The flight crew stopped the climb and completed the memory items necessary to shut down the left engine. While on vectors for the return, the flight crew lost visual reference with the runway temporarily and regained it at 0.8 nautical miles from the threshold. Air traffic control cleared the aircraft for a contact approach to Runway 08. The flight crew conducted a single-engine landing on Runway 08. At 0212, following touchdown 9075 feet down the wet runway, the aircraft overran the runway by approximately 40 feet, striking 2 runway end lights and coming to a stop on the prepared surface. There were no injuries. The aircraft sustained minor damage.

1.0 Factual information

1.1 History of the flight

1.1.1 Background

On 12 April 2024, at 2235 Atlantic Daylight Time,All times are Atlantic Daylight Time (Coordinated Universal Time minus 3 hours). the Keewatin Air LP (Keewatin Air) Beechcraft King Air B200 (King Air B200) aircraft departed Iqaluit International Airport (CYFB), Nunavut, on an instrument flight rules (IFR) medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) flight with a final destination of Ottawa/MacDonald-Cartier International Airport (CYOW), Ontario. The flight required fuel stops at Goose Bay Airport (CYYR), Newfoundland and Labrador, and at Quebec/Jean Lesage International Airport (CYQB), Quebec. On board were 2 flight crew members, 2 medical staff, and 1 patient.

The 1st leg of the flight was uneventful, and the aircraft landed at CYYR at 0116 on 13 April 2024. The fuel tanks were fully refuelled.

An automatic aerodrome routine meteorological report (METAR AUTO) was issued at 0200, 2 minutes before the flight crew started the engines for the next leg of the flight. It indicated winds from 140° true (T) at 8 knots, no precipitation, and an altimeter setting of 29.83 inches of mercury (inHg). About 2 hours before, another METAR AUTO had reported light rain showers.

1.1.2 Occurrence flight

At 0204, the flight crew started the taxi for Runway 26 and departed 2 minutes later for CYQB. The first officer (FO) was the pilot flying (PF). Once the aircraft was airborne, the flight crew contacted air traffic control (ATC) in Gander, Newfoundland and Labrador, indicating that they were at 700 feet above sea level (ASL). When ATC cleared the occurrence aircraft to CYQB, the flight crew received a left engine fire annunciator light indication and perceived a burning smell. When the aircraft was approximately 1200 feet ASL, the flight crew requested a return to CYYR visually onto the reciprocal runway (08) and subsequently declared an emergency.

The flight crew levelled off at approximately 2200 feet ASL and performed the memory items from the checklist for an engine fire in flightSee Section 1.17.2.2 Standard operating procedures for engine fire in flight of the report. to shut down the left engine.

ATC asked the flight crew if they were able to conduct the visual approach or if they would like a radar vector. The flight crew accepted ATC’s offer for vectors, and the controller cleared the aircraft to climb to 3100 feet ASL and to turn right to head north.

The flight crew requested to remain at their present altitude because they were just at the base of the clouds. ATC inquired as to whether they had the field in sight, or if they were able to conduct a contact approach.Section 9.6.1: Contact Approach of Transport Canada’s TP 14371E, Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM), RAC – Rules of the Air and Air Traffic Services (21 March 2024) states that “A contact approach is an approach wherein an aircraft on a IFR flight plan or flight itinerary having an ATC clearance, operating clear of clouds with at least 1 NM flight visibility and a reasonable expectation of continuing to the destination airport in those conditions, may deviate from the IAP [instrument approach procedure] and proceed to the destination airport by visual reference to the surface of the earth.”. The flight crew replied that they had visual contact with the ground. However, the broken cloud layer made it difficult for the flight crew to maintain constant ground contact throughout the vectors to final.

The air traffic controller assisted the flight crew with vectors and relaying distance back from the field. The flight crew started a slow descent and, on final, when ATC informed them that they were 2 nautical miles (NM) from the airport, the flight crew increased their rate of descent to greater than 1000 fpm.

At 0211, when the aircraft was 1.2 NM from the threshold of Runway 08, ATC asked the flight crew whether they were able to conduct the approach from there. At that time, the aircraft was approximately 1600 feet ASL, with a ground speed of 198 knots and a rate of descent of 2300 fpm.

At 0.8 NM from the runway, the flight crew replied they were able to conduct the approach, and ATC cleared them for the contact approach and instructed them to switch over to the CYYR tower.

The aircraft was then approximately 1350 feet above sea level (ASL) with the same ground speed (198 knots) and a rate of descent of over 2200 fpm. The rate of descent increased to over 2900 fpm as they continued toward the runway.

When the aircraft approached the runway, it was approximately 340 feet left of the centreline. The flight crew initiated a right roll to align with the runway. The aircraft crossed the runway threshold at approximately 400 feet AGL (560 feet ASL) with a groundspeed of 200 knots and a rate of descent of over 2300 fpm.

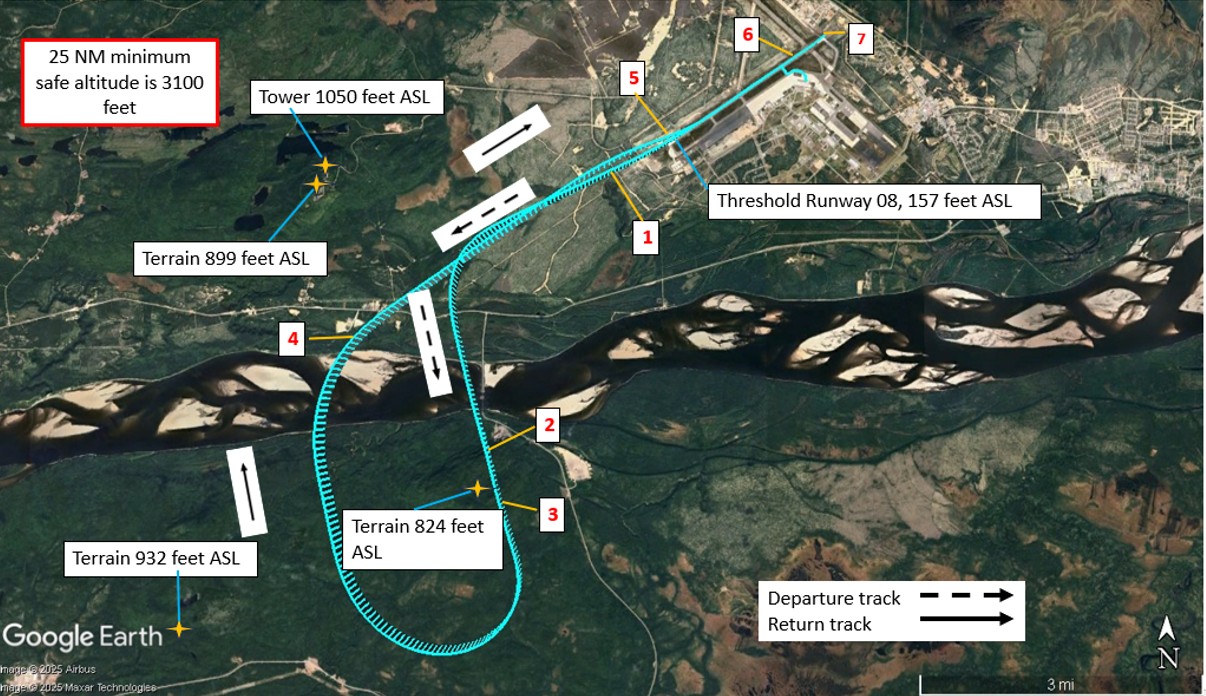

At 0212, almost 6 minutes after taking off, the aircraft touched down on Runway 08, approximately 9075 feetAccuracy is ±200 feet because of the speed of the aircraft and the recorded data sample rate. from the threshold, with 1975 feet remaining, at a speed of about 96 knotsThe normal landing speed, based on the weight of the aircraft, was 103 knots. (Figure 1).

Legend

Aircraft departing from Runway 26.

Left engine shutdown.

Aircraft at 2175 feet ASL; 190 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS); 157 knots ground speed; 143 fpm rate of descent.

Aircraft at 3.2 NM from threshold; 2090 feet ASL; 177 KIAS; 200 knots ground speed; 239 fpm rate of descent.

Aircraft 340 feet left of the centreline abeam the threshold; 201 KIAS; 199 knots ground speed; 560 feet ASL; 2800 fpm rate of descent.

Note: Maximum rate of descent on final at 0.2 NM was 2969 fpm.Touchdown past Taxiway B; 1975 feet before the end of Runway 08; about 96 knots ground speed.

Aircraft stopped about 40 feet past the runway end lights.

The runway was wet; the aircraft experienced hydroplaning. The PF used brakes and various reverse thrust amounts on the right engine while trying to maintain directional control when the aircraft started to slide, first yawing to the left, then to the right. Full reverse could not be continually applied given the adverse effect on directional control.

As the aircraft was nearing the end of the runway, it continued to slide sideways and exited the end of the runway at a speed of approximately 20 knots. The right propeller and left main gear hit 2 runway end lights. The aircraft came to a stop on the prepared surface, about 40 feet beyond the end of the runway (Figure 2).

Airport rescue and fire fighting personnel responded quickly, arriving within 1 minute because the crash alarm had been activated by the tower controller when the emergency was declared.

There were no injuries. The aircraft sustained minor damage.

1.2 Injuries to persons

There were no injuries.

1.3 Damage to aircraft

During the runway overrun, 2 adjacent propeller blades on the right propeller hit a runway end light, causing the blade tips to bend and the blades to incur gouge marks. The propeller damage was beyond field repair limitations, and the propeller was replaced. The right engine was replaced to complete the sudden stoppage inspection required following the propeller strike.

Each of the 4 main landing gear tires on the aircraft exhibited a patch of reverted rubber associated with reverted-rubber hydroplaning (Figure 3).

1.4 Other damage

Two runway end lights required replacement after incurring damage from the impact with the occurrence aircraft’s left main landing gear tires and the right propeller.

1.5 Personnel information

Captain | First officer | |

|---|---|---|

Pilot licence | Commercial pilot licence (CPL) | Airline transport pilot licence (ATPL) |

Medical expiry date | 01 October 2024 | 01 March 2025 |

Total flying hours | 1502.9 | 1686 |

Flight hours on type | 910.3 | 1163.9 |

Flight hours in the 24 hours before the occurrence | 3.3 | 3.3 |

Flight hours in the 7 days before the occurrence | 33.8 | 33.8 |

Flight hours in the 30 days before the occurrence | 80.7 | 80.7 |

Flight hours in the 90 days before the occurrence | 187.1 | 168.8 |

Flight hours on type in the 90 days before the occurrence | 187.1 | 168.8 |

Hours on duty before the occurrence | 6.5 | 6.5 |

Hours off duty before the work period | 16.4 | 16.4 |

The flight crew held the appropriate licences and ratings for the flight in accordance with existing regulations.

The captain joined Keewatin Air as an FO in September 2022 and upgraded to captain in June 2023.

The FO joined Keewatin Air in August 2023 and was captain-qualified. On the occurrence flight, the FO was the PF and was occupying the right seat.

According to Keewatin Air’s records, the captain and the FO had received their most recent crew resource management (CRM) training on 15 May 2023 and on 11 September 2023, respectively. The occurrence flight was the 1st time that the flight crew had flown into CYYR.

1.6 Aircraft information

Manufacturer | Beech Aircraft Corporation* |

Type, model, and registration | King Air, B200, C-GBYN |

Year of manufacture | 1985 |

Serial number | BB 1232 |

Certificate of airworthiness | 05 June 2003 |

Total airframe time | 25 306.0 hours |

Engine type (number of engines) | Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-42 (2) |

Propeller type (number of propellers) | Hartzell Propeller Inc. HC-D4N-3A (2) |

Maximum allowable take-off weight | 12 500 lb (5669.9 kg) |

Recommended fuel types | Jet A, Jet A-1 |

Fuel type used | Jet A-1 |

* Textron Aviation Inc. (Textron Aviation) currently holds the type certificate for the aircraft type.

1.6.1 General

The King Air B200 is a pressurized, twin-engine, turboprop, fixed-wing aircraft. The occurrence aircraft was configured to conduct the MEDEVAC flight of a patient with a flight crew of 2 pilots and 2 medical staff.

There were no recorded defects outstanding at the time of the occurrence, and the investigation did not identify any issues related to aircraft equipment, maintenance, or certification that would have prevented the aircraft from operating normally during the occurrence flight. The aircraft’s weight and centre of gravity were within the prescribed limits.

1.6.2 Propeller reverse

The occurrence aircraft’s engines each had a 4‑aluminum-blade constant-speed reversing propeller installed.The Hartzell lightweight HC-D4N-3A propellers were installed in accordance with Raisbeck Engineering Supplemental Type Certificate SA2698NM-S.

Propeller rotational speed within the governing range remains constant at the speed selected by a pilot using the propeller control levers.

Reverse thrust is achieved on the ground by retarding the power levers below the IDLE position. The power levers must be raised to move them past the IDLE detent, where retarding them initially increases engine speed (Ng) and also moves the beta valve on the propeller governor to decrease the propeller blade low-pitch setting toward decreased blade angles. This is referred to as ground beta range. Further retarding the power levers moves the propeller blade low-pitch setting to allow negative blade pitch angles and increased Ng in this reversing range. Reverse thrust power increases in direct proportion to the further retarding of the power levers.Raytheon Aircraft Company, Beechcraft Super King Air B200 & B200C Pilot’s Operating Handbook and FAA Approved Airplane Flight Manual (Revised August 2004), section VII: Systems Description, p. 7-24.

1.6.3 Main landing gear brakes and tires

The King Air B200 has 2 tires on each main gear leg, and the occurrence aircraft was equipped with optional high-floatation tires.The high-floatation tires are larger (22x6.75-10 vs 18x5.5 Type VII), 8-ply-rated, and tubeless tires.

The King Air B200 uses a dual hydraulic brake system that is operated by depressing the toe portion of either the pilot's or copilot's rudder pedals. A shuttle valve enables braking by either the pilot or copilot. Hydraulic pressure from the left or right pedal force actuates its respective left or right brake caliper and brake disc assemblies.Raytheon Aircraft Company, Beechcraft Super King Air B200 & B200C Pilot’s Operating Handbook and FAA Approved Airplane Flight Manual (Revised August 2004), section VII: Systems Description, p. 7-15.

The occurrence aircraft was not equipped with an anti-skid braking system.

Keewatin Air maintenance inspected the aircraft’s wheels and brakes for damage and condition following the occurrence. Additionally, the aircraft braking system was taxi-tested for brake operation, and no faults were noted.

After the occurrence, each of the 4 main landing gear tires on the aircraft exhibited a patch of reverted rubber. Maintenance personnel evaluated them to be within service limits.

1.6.4 King Air B200 fire detection and extinguisher systems

1.6.4.1 Typical system

The King Air B200 is equipped with a fire detection system designed to provide the pilots with an immediate warning in case of fire in either engine compartment. Typically, for each engine,It is the case of engines used on King Air B200 aircraft serial numbers BB-2 to BB-1444, except 1439. the system uses 3 photoconductive flame detectors that are sensitive to infrared radiation. These flame detectors are positioned within the engine compartment to receive both direct and reflected rays in order to monitor the entire compartment for fire. Conductivity through the flame detector varies in direct proportion to the intensity of the infrared radiation striking the detector. When the signal strength reaches a preset level, a relay in the flame detection control amplifier closes to illuminate the appropriate left- or right-engine warning annunciator (placarded L ENG FIRE and R ENG FIRE). A single test switch placarded TEST SWITCH - FIRE DET & FIRE EXT is located on the inboard side of the copilot's subpanel and has 6 positions: system off, left/right extinguisher, and flame detectors 3, 2, and 1.The positions 3, 2, and 1 each test one of the 3 photoconductive flame detectors.

An optional engine fire extinguisher system may be installed on the King Air B200 aircraft. This system uses a pyrotechnic cartridge to discharge an extinguishing agent through a network of plumbing from a fire extinguisher cylinder located inside the engine nacelle to spray nozzles strategically positioned within the engine compartment. The optional fire extinguisher system is actuated by 2 control switches located on the glare shield at each end of the warning annunciator panel.

If the optional engine fire extinguisher system is not installed, the RIGHT EXT and LEFT EXT positions on the left side of the test switch will not be installed.Raytheon Aircraft Company, Beechcraft Super King Air B200 & B200C Pilot’s Operating Handbook and FAA Approved Airplane Flight Manual (Revised August 2004), section VII: Systems Description, p. 7-29.

Each engine’s fire extinguisher control switch is made up of 3-colour lenses located under a clear plastic cover (Figure 4). To discharge the cartridge, the pilot would raise the witness-wired clear plastic cover and press the face of the appropriate lens. The fire extinguisher is a one-shot system and will be completely expended upon activation.Ibid., p. 7-30.

The red lens, placarded L (or R) ENG FIRE - PUSH TO EXT, illuminates if a flame detector is actuated. The amber lens, placarded D, illuminates if the system has been discharged, and the supply cylinder is empty. The green lens, placarded OK, is provided only for the test function, which is used to test the illumination of the bulbs and the circuitry of the system (Figure 4).

The test switch (TEST SWITCH - FIRE DET & FIRE EXT) is used to verify the fire extinguisher system circuitry for serviceability. During the pre-flight checks, the pilot is to rotate the test switch to the 2 positions (RIGHT EXT and LEFT EXT) to check that the amber D lens and the green OK lens on each fire extinguisher control switch on the glare shield illuminates.Ibid.

1.6.4.2 Occurrence aircraft’s system

The occurrence aircraft was originally exported to the United Kingdom, where it was equipped with 4-flame detectors on each engine per United Kingdom certification requirements. The aircraft also had an optional fire extinguisher system that uses 2 test switches, each with 6 positions: system off, left/right extinguisher, and flame detectors 4, 3, 2, and 1. The occurrence aircraft is the only King Air B200 in Keewatin Air’s fleet with the 2-test-switch, 4-flame-detector system (Figure 5).

The investigation could not determine whether the flight crew completed the test of the fire detection and extinguisher systems during the pre-flight inspection checklist on the day of the occurrence.

Following the occurrence, no signs of heat or fire damage were found in the left-engine nacelle. An inspection of the left-engine fire detection system found abraded wire insulation on the left-engine lower aft flame detector. It was determined that this wire was chafing and made electrical contact with the left-engine firewall, resulting in the left-engine fire indication.

1.6.5 Warning annunciator system

When an aircraft system fault condition monitored by an annunciator system occurs, a signal is generated, and the appropriate annunciator is illuminated. Annunciators for faults that require immediate attention are placed in the warning annunciator panel, centrally located in the instrument glare shield (Figure 6).

Warning annunciators are illuminated in red with text that indicates a system fault. For engine fires, 2 warning annunciators (L ENG FIRE and R ENG FIRE) are provided.

In addition, the system includes 2 MASTER WARNING flashers, each located on the outer ends of the glare shield that flash when a warning annunciation occurs (Figure 7).Ibid., p. 7-6.

Being on the glare shield, the warning ENG FIRE annunciators and MASTER WARNING flashers are clearly visible to the pilots with no obstruction to vision.

The aircraft flight manual indicates the following:

Any illuminated lens in the warning annunciator panel will remain on until the fault is corrected. However, the MASTER WARNING flashers can be extinguished by depressing the face of either MASTER WARNING flasher, even if the fault is not corrected. In such a case, the MASTER WARNING flashers will again be activated if an additional warning annunciator illuminates and will continue flashing until one of them is depressed.Ibid.

A fire detection system activation will cause its associated (L ENG FIRE or R ENG FIRE) warning annunciator to illuminate, along with the MASTER WARNING flashers.

During the occurrence, the L ENG FIRE annunciator, the MASTER WARNING flasher, and the left ENG FIRE - PUSH TO EXT light illuminated.

1.7 Meteorological information

The METAR AUTO for CYYR issued at 0200 indicated the following:

- Winds from 140°T, at 08 knots

- Visibility 15 statute miles (SM)

- Few clouds at 500 feet above ground level (AGL) (660 feet ASL), broken ceilingBroken clouds are reported as 5 to 7 oktas of cloud cover, meaning that the sky is covered between 5/8 and less than 8/8 with clouds. at 1300 feet AGL (1460 feet ASL), and overcast cloud layer at 2500 feet AGL (2660 feet ASL)

- Temperature 5 °C and dew point 3 °C

- Altimeter setting 29.83 inHg

The METAR AUTO included a remark indicating that the ceiling was an estimation.

An aerodrome special meteorological report (SPECI) was issued at 0212 (i.e., the time of the occurrence); it indicated the same weather, apart from the winds being from 120°T at 4 knots, and the temperature being 4 °C.

Before the occurrence, there had been some light rain showers at the airport off and on throughout the evening and night, with the precipitation ending at 0022.

The investigation was unable to determine what weather information the pilots obtained or reviewed before the occurrence.

1.8 Aids to navigation

The following instrument approaches are available at CYYR:

- Area navigation global navigation satellite system (RNAV GNSS), for all 4 runways

- Category I instrument landing system (ILS) (version Z) for Runway 08

After they declared the emergency, the flight crew did not input an emergency return approach into their global positioning system (GPS) for Runway 08.

1.9 Communications

There were no known communication difficulties.

1.10 Aerodrome information

CYYR is operated by Canadian Forces Base Goose Bay. Aircraft rescue and fire fighting service is provided by the Canadian Armed Forces.

The aerodrome elevation is 160 feet ASL. CYYR has 2 runway surfaces: Runway 08/26 and Runway 15/33, both in concrete with asphalt overlay and 200 feet wide. The 2 runways are 11 052 and 9584 feet long respectively and have a 300 m prepared surface at both ends.

1.11 Flight recorders

The occurrence aircraft was not equipped with a cockpit voice recorder (CVR) or a flight data recorder (FDR), nor was either required by regulation. The aircraft was, however, equipped with a Garmin G1000 avionics suite and a SKYTRAC ISAT-200A satellite transceiver / flight data acquisition unit. Both units were recovered and sent to the TSB Engineering Laboratory in Ottawa, Ontario, for data recovery and examination. The data recovered included the aircraft’s flight data (e.g., aircraft track, altitude, longitudinal/lateral/yaw accelerations, engine operational parameters).

1.12 Wreckage and impact information

Not applicable.

1.13 Medical and pathological information

There was no indication that the flight crew’s performance was negatively affected by medical or physiological factors, including fatigue.

1.14 Fire

There was no indication of fire after the occurrence.

1.15 Survival aspects

Not applicable.

1.16 Tests and research

1.16.1 TSB laboratory reports

The TSB completed the following laboratory reports in support of this investigation:

- LP057/2024 – Runway Overrun Analysis

- LP062/2024 – NVM Data Recovery – Flight Tracker

1.17 Organizational and management information

1.17.1 Operator

Keewatin Air operates primarily in the Arctic under Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs) subparts 703 (Air Taxi Operations) and 704 (Commuter Operations). Keewatin Air provides charter services, but its primary focus is medical transportation and air ambulance services. At the time of the occurrence, Keewatin Air’s MEDEVAC fleet was comprised of King Air B200s, Pilatus PC-12s, Pilatus PC24s, and Cessna Citation 560s.

1.17.2 Training

1.17.2.1 Differences in the fleet and in training

The King Air B200 is a highly versatile aircraft, with many units produced. Its versatility has resulted in a wide range of modifications and options. Given these varied aircraft configurations, not all 15 King Air B200 aircraft in the Keewatin fleet are identical.

To assist its pilots in identifying the differences between each aircraft, Keewatin Air provides a chart in the King Air 200 and B200 pilot checklist.Keewatin Air LP, BEECHCRAFT KING AIR Model 200 & B200 With Garmin G1000Nxi, Revision 0, p. S-2. Examples of differences between aircraft include the types of landing gear actuation, the number of blades on the propellers, any leading-edge modifications, and other options such as an engine fire extinguisher.

The chart in use at the time of the occurrence indicated that 2 aircraft in Keewatin Air’s fleet were equipped with engine fire extinguishers, when in fact 5 of the 15 King Air B200 aircraft were so equipped. The 2 aircraft listed as being equipped with engine fire extinguishers were the occurrence aircraft and 1 aircraft that was no longer in the fleet.

King Air B200 pilots at Keewatin Air are provided training in flight simulators in Wichita, Kansas, United States. The training is conducted with Keewatin Air training personnel. The simulator used for training the occurrence pilots was not equipped with all of the modifications and options for each aircraft in the King Air B200 fleet and was not equipped with engine fire extinguishers. Because of this, during ground school, Keewatin Air provided the occurrence pilots with training on differences in equipment installed in all aircraft of the same type in the company’s fleet, including training on the engine fire extinguishing system. This training did not identify the peculiarity of the occurrence aircraft’s detection and suppression system, with the 4-flame detectors and 2 test switches.

1.17.2.2 Standard operating procedures for engine fire in flight

Standard operating procedures (SOPs) are vital sources of information that provide pilots with guidelines on general use of the aircraft. They assist pilots with decision making and coordination between flight crew members.

The Keewatin Air SOPs include a section on abnormal operations. This section expands on checklists that contain memory items, including engine fire during an in-flight emergency.

The illumination of the ENG FIRE lights means that the fire detection system has been actuated, indicating a potential engine fire. In this situation, the SOPs instruct the flight crew to go through the memory items and then to go through the emergency engine shutdown checklist (Table 3).

PF | PILOT MONITORING (PM) |

|---|---|

“IDENTIFY AND CANCEL” | “MASTER WARNING – LEFT/RIGHT ENGINE FIRE CANCELLED” Cancels the Master Warning |

“AUTOPILOT DISCONNECT”, while pressing and releasing AP/YD DISC/TRIM INTRPT [autopilot/yaw damper disconnect/trim interrupt] Button

“ENGINE FIRE. SET MAX POWER”

| Set max power “MAX POWER SET” |

“MEMORY CHECKS LEFT/RIGHT ENGINE FIRE” | |

“CONFIRM FUEL CUT OFF” | “LEFT/RIGHT CONDITION LEVER” Moves Condition Lever to Cut Off |

“CONFIRM FEATHER” | “LEFT/RIGHT PROPELLER LEVER” Moves Propeller Lever to Feather |

CAPTAIN | FIRST OFFICER |

“LEFT/RIGHT FIREWALL SHUT OFF VALVE” Select the Firewall Shut off Valve to Closed | “CONFIRM CLOSE” |

PF | PM |

“FIRE STATUS” | “NO FIRE” |

“MEMORY CHECKS COMPLETE” | |

“MAX CONTINUOUS POWER” (or power as required if max continuous is not required). “EMERGENCY ENGINE SHUTDOWN CHECKLIST” | Sets max continuous power. “MAX CONTINUOUS POWER SET”

|

On the following page, the SOPs continue with a listing of the memory items if the aircraft on fire is equipped with fire extinguishers. In that case, the memory items require the flight crew to actuate the fire extinguisher before referring to the emergency engine shutdown checklist (Table 4).

Memory Checks If On Fire (For Aircraft Equipped With Fire Bottles) | |

|---|---|

PF | PM |

“CONFIRM ACTUATE” | “LEFT/RIGHT ENGINE IS ON FIRE. LEFT/RIGHT FIRE EXTINGUISHER” Discharges bottle |

“MEMORY CHECKS COMPLETE” | |

“MAX CONTINUOUS POWER” (or power as required if max continuous is not required)” “EMERGENCY ENGINE SHUTDOWN CHECKLIST” | Set max continuous power “MAX CONTINUOUS POWER SET”

|

In addition, the pilot checklist that is used in the cockpit identifies the procedures to be used in an emergency and highlights memory items in bold. The checklist for an engine fire in flight is included under the ENGINE FAILURE section, which is divided into 2 subsections: the 1st subsection is called EMERGENCY ENGINE SHUTDOWN, which applies to various conditions, including engine fire/failure in flight, and the 2nd subsection is called ENGINE FIRE IN FLIGHT. Both subsections refer the pilots to page A-5 for the one-engine-inoperative approach-and-landing checklist (Figure 8).

In this occurrence, the pilots performed the bolded memory items 1 to 4 under the EMERGENCY ENGINE SHUTDOWN subsection on the checklist. They did not perform item 5 to actuate the fire extinguisher.

1.17.3 Stable approach

International research in 2013 indicated that among commercial operators, 3.5% to 4% of approaches were unstable.Flight Safety Foundation, “Failure to Mitigate,” in AeroSafety World (February 2013). Of these, 97% were continued to a landing, with only 3% resulting in a go-around, despite airlines' stable-approach policies. As reported in previous investigations by the TSBTSB air transportation safety investigation reports A20Q0013, A15O0015, A14W0127, A14Q0148, A14F0065, A13O0098, A12Q0161, A12P0034, A12O0005, A12W0004, and A11H0002. and other foreign agencies, the negative outcomes of unstable approaches include tail strikes, runway overruns, and controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). As a result of this knowledge, significant improvements have been made by industry to reduce unstable approach accidents.

The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) describes a stabilized approach as:

a key feature to a safe approach and landing. Operators are encouraged by the FAA and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) to use the stabilized approach concept to help eliminate CFIT. The stabilized approach concept is characterized by maintaining a stable approach speed, descent rate, vertical flightpath, and configuration to the landing touchdown point.Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Advisory Circular (AC) 120-108: Continuous Descent Final Approach (20 January 2011), p. 2, at https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC_120-108.pdf (last accessed on 24 December 2025).

Keewatin Air’s policy on stable approaches indicates that “unstable approaches are frequent factors in approach-and-landing accidents, including those involving controlled flight into terrain (CFIT).”Keewatin Air LP, Company Operations Manual, Amendment 3 (25 March 2022), section 7.3.8: Stable Approach Policy, p. 7-11.

In addition, the company SOPs include the following:

An approach is stabilized when all the following criteria are met:

a) The aircraft is on the correct flight path;

b) Only small changes in heading/pitch are required to maintain the correct flight path;

c) The aircraft speed is not more than VREF [landing reference speed] + 20 knots indicated airspeed and not less than VREF crossing the FAF [final approach fix] or FAWP [final approach waypoint] inbound;

d) The aircraft is in its final landing configuration. Changes to landing configuration after passing the FAF or FAWP constitutes an unstable approach and therefore, a missed approach/go-around must be initiated;

e) Sink rate is no greater than 1,000 feet per minute. If an approach requires a sink rate greater than 1,000 feet per minute, a special briefing should be conducted;

f) Power setting is appropriate for the aircraft configuration and is not below the minimum power for approach as defined by the aircraft operating manual;

g) All briefings and checklists have been conducted;[…]Ibid., section 6.24.4: Stabilized Approaches, p. 6-53.

These criteria are also found in the SOPs, which include the following:

An approach that becomes unstabilized below 1,000 feet above airport elevation in IMC [instrument meteorological conditions] or below 500 feet above airport elevation in VMC [visual meteorological conditions] requires an immediate go-around. At the minimum stabilization height and below, a go-around call should be made by the Pilot Monitoring (PM) if any flight parameter exceeds the criteria shown above.Ibid. [emphasis in original]

1.18 Additional information

1.18.1 Minimum sector altitude

The minimum sector altitude (MSA) is “[t]he lowest altitude that will provide a minimum clearance of 1000 ft […] above all objects located in an area contained within a sector of a circle with a 25 NM radius centred on a radio aid to navigation or a specified point [i.e., a waypoint located near the aerodrome]”.Transport Canada, TP 14371, Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM), GEN – General (21 March 2024), section 5.1: Glossary of aeronautical terms.

In this occurrence, the MSA for the area was 3100 feet ASL, which is the altitude at which ATC provided clearance. The aircraft levelled off at around 2200 feet ASL, remaining below the MSA during the return to CYYR.

1.18.2 Aircraft braking performance calculation

The King Air B200/B200C aircraft flight manual includes landing performance charts to provide conventional landing distances.Raytheon Aircraft Company, Beechcraft Super King Air B200 & B200C Pilot’s Operating Handbook and FAA Approved Airplane Flight Manual (Revised August 2004), section V: Performance, pp. 5-120 to 5-124. The performance charts provide landing data with or without propeller reversing, and with flaps up and full flaps down configurations. The charts assume that the runway is dry. The aircraft flight manual does not provide any charts for wet runways, nor does it provide charts for single-engine landings.

The investigation calculated the landing distance at the time of the occurrence using performance charts and values and determined that, for a landing with no propeller reversing on a dry runway in a full-flap-down configuration (with both engines running), the landing roll would be approximately 1600 feet.

The investigation team asked Textron Aviation to provide the TSB with braking performance values for both dry and wet runway scenarios because there was no published wet runway data for the accident aircraft. To estimate wet runway conditions the aircraft manufacturer used guidance and data from the Beechcraft Super King Air (B300) to develop approximate numbers for the B200 aircraft. The landing is split into 2 distinct segments, air distance and landing roll, and the calculations are based on runway conditions and whether the reverse thrust is used or not. The landing roll is computed assuming a constant deceleration and is corrected for a non-level runway slope.

Textron Aviation used the following specifications to determine the distances:

- Temperature: 4 °C

- Weight: 12 500 pounds

- Winds: 2-knot tailwind

- Gradient: 0°

- Rate of descent without reverse thrust: −800 fpm

- Rate of descent with reverse thrust: −1000 fpm

Table 5 shows the performance breakdown values provided by Textron Aviation.

Engines | Runway condition | Air distance (feet) | Landing roll (feet) | Total distance (feet) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Multi-engine without reverse thrust | Dry | 1100 | 1700 | 2800 |

Wet | 1100 | 3200 | 4300 | |

Multi-engine with reverse thrust | Dry | 1000 | 1100 | 2100 |

Wet | 1000 | 2100 | 3100 |

The most relevant distance for the occurrence flight would be the multi-engine aircraft landing on a wet runway without reverse thrust, which would result in a landing roll of 3200 feet. However, the occurrence aircraft landed with a single engine and inconsistent application of reverse thrust.

Limited use of reverse thrust will lengthen the landing roll. Therefore, the investigation could not accurately determine the actual distance that the aircraft required to stop, but once the aircraft touched down, the maximum runway length remaining was 1975 feet (±200 feet).

1.18.3 Hydroplaning

Hydroplaning, also known as aquaplaning, occurs when a film of water forms between the airplane’s tires and the runway surface, causing a loss of traction and preventing the airplane from responding to control inputs such as steering and braking.

Generally, there are 3 distinct types of hydroplaning, which are described as follows:

- Viscous hydroplaning occurs at a relatively low speed on a wet runway. The friction between the tire and runway is reduced, but not to a level that impedes the wheel rotation.

- Reverted-rubber hydroplaning happens when a locked tire skids along the runway surface. This generates enough heat to change water into steam and to melt (revert) rubber to its original uncured state. Only this type of hydroplaning produces a clear mark on the tire tread in a form of a burn (a spot of reverted rubber) and possibly steam-cleaned marks on the runway when sufficient heat is generated between the tire and the runway to change the water into steam.

- Dynamic hydroplaning is when the tire lifts off the pavement and rides on a wedge of water like a water ski. Because the conditions required to initiate and sustain dynamic hydroplaning are extreme, the phenomenon rarely occurs. When dynamic hydroplaning occurs, it lifts the tire completely off the runway and causes a substantial loss of friction between the tire and the runway surface. Under these conditions, wheel spin-up may not occur and braking forces are negligible.

The TSB laboratory determined that there was a strong possibility that dynamic hydroplaning occurred during the first 3 seconds after touchdown. Because of this, it is possible that during these 3 seconds, the aircraft experienced minimal braking capability, increasing the landing roll.

There was evidence of reverted-rubber hydroplaning noted on all 4 main landing gear tires. Based on the sideways skidding that occurred, the aircraft most likely did not have traction during the final stages of the landing roll and, therefore, had reduced braking capability, which would have further increased the landing roll.

1.18.4 Speed–accuracy trade-off

The speed–accuracy trade-off is the observation that, because of limited cognitive capacity, the speed at which a task is performed has a direct relationship with the accuracy with which that task is performed.P. M. Fitts, “The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement,” Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol. 47, No 6 (June 1954), pp. 381-391. In general, tasks can be completed quickly with more errors or slowly with fewer errors; either speed or accuracy will be sacrificed when prioritizing the other. The speed–accuracy trade-off is observed in simple motor and physical tasksJ. T. Fairbrother, Fundamentals of Motor Behavior (2010). and in complex cognitive tasks, including the control of aircraft.C. D. Wickens, M. A. Vidulich, and P. S. Tsang, “Information processing in aviation,” in J. R. Keebler, E. H. Lazzara, K. A. Wilson et al. (eds.), Human Factors in Aviation and Aerospace (Academic Press, 2023), pp. 89-139.

Speed-accuracy trade-offs are commonly observed in situations where people are required to perform under time pressure. For example, a pilot under stress caused by an emergency may perform a series of tasks quickly, but with errors (e.g., incorrect ordering of sub-tasks, substantive deviations from acceptable limits). However, the magnitude of the speed–accuracy trade-off can be reduced by increasing experience on a task through practice.M. Kasiri, E. Biffi, E. Ambrosini et al., “Improvement of speed-accuracy tradeoff during practice of a point-to-point task in children with acquired dystonia,” Journal of Neurophysiology (02 October 2023), Vol. 130, Issue 4, pp. 931-940. Therefore, if completion speed is held constant, a highly practised task will be completed with fewer errors than a task that has not been practised as often.

1.18.5 Cognitive tunnelling

The limits of human attention are responsible for the cognitive tunnelling effect. Our expectations and experiences control how attention is focused on some information in the environment, but not on other information. When information in the environment is not attended, it never reaches a point where a person becomes aware of it. This failure to process information leads to inattentional blindness,A. Mack and I. Rock, Inattentional blindness (The MIT Press, 1998). a phenomenon where some information is not processed, despite it being in plain sight. An aircraft pilot can therefore be functionally blind to clearly visible information on their flight display if they are cognitively tunnelled on other information.

1.18.6 Confirmation bias

Human decision-makers tend to rely on heuristics – or shortcuts – in order to simplify the process of separating signal (i.e., information that is relevant to their decision) from noise (i.e., ambiguous or irrelevant information). These mental shortcuts are beneficial in the sense that they often lead to fast and accurate decisions, but are susceptible to many forms of cognitive biases, which can lead to errors. A confirmation bias is a cognitive bias where ambiguous or non-diagnostic evidence is interpreted as being consistent with existing beliefs or hypotheses.R. S. Nickerson, “Confirmation bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises,” Review of General Psychology, Vol. 2, No. 2 (1998), pp. 175–220. For example, if a pilot believes that their aircraft is experiencing a mechanical failure, it is likely that a subset of the information being processed by that pilot – which, under normal operating conditions, would be mentally categorized as ambiguous or not associated with a mechanical failure – would now be interpreted as confirmatory evidence of that mechanical failure.

Moreover, it has been shown that confirmation bias can occur across different sensory modalities. For example, olfactory information (i.e., smell) can influence a decision that is primarily based on visual information and vice versa. The cross-modal linkage between the olfactory and visual senses is understood as a cognitive mechanism whereby olfactory cues guide visual attention.A. Seigneuric, K. Durand, T. Jiang et al., “The nose tells it to the eyes: Crossmodal associations between olfaction and vision, Perception, Vol. 39 (2010), pp. 1541-1554.

1.18.7 Recognition-primed decision making

Recognition-primed decision making (RPD) is a theoretical model that was developed to explain how people make efficient decisions in complex and dynamic environments.G. A. Klein, “A recognition-primed decision (RPD) model of rapid decision making,” Decision Making in Action: Models and Methods, section B: Models of naturalistic decision making, article 6 (1993), pp. 138-147. RPD proposes that decisions are based on what people perceive about the world, which depends on what information is attended. The RPD model further assumes that the control of attentional resources is an implicit compromise between attending to stimuli that are expected and being prepared to encode conflicting information that may force the observer to deviate from their current understanding of the situation.

In most cases, an observer’s decision is based on the 1st mental model – or schema – that adequately fits their perception of the external environment. This approach to decision making is largely out of the conscious control of the observer and has developed to allow past experience and accrued knowledge to guide humans in situations that demand prompt responses. The alternative is to scan the environment with deliberate attentional control to parse a potentially meaningful signal from background noise, process the signal to determine its relevance to the current situation, and then integrate the relevant signal into an updated mental model. The alternative to RPD is a more effortful and time-consuming process that requires an observer to scan the environment to identify relevant information. This alternative is often counterproductive in situations that require fast decision making (e.g., when piloting an aircraft). Indeed, relying on this slower and more effortful approach can be detrimental in high workload conditions where other competing high-importance tasks require timely and accurate responses.

2.0 Analysis

The occurrence flight crew held the appropriate licence and ratings for the flight in accordance with existing regulations, and there was no indication that their performance was degraded by fatigue. The investigation did not identify any issues related to aircraft equipment, maintenance, or certification that would have prevented the aircraft from operating normally during the occurrence flight, and the investigation found no sign of actual engine fire.

Post-occurrence inspection revealed chafing of the wire harness on the left-engine lower aft flame detector that likely made electrical contact with the left-engine firewall, resulting in a left-engine fire indication. Consequently, the analysis will focus on the flight crew’s response when they received the engine fire indication, the factors associated with the urgency to land, the flight crew’s risk perception and decision-making (including deviations from the stabilized approach criteria), and finally training on a fleet of aircraft with different equipment.

2.1 Engine fire indication

The aircraft made an uneventful stop at the Goose Bay Airport (CYYR), Newfoundland and Labrador, to refuel. Given the light winds, the flight crew had the flexibility to depart from Runway 26, in the direction of their destination and with a shorter taxi. After takeoff at 0206, while climbing through 700 feet above sea level (ASL), the left-engine fire warning annunciator illuminated.

In addition to the illumination of the master warning flasher and engine fire warning annunciator, the flight crew perceived a burning smell during takeoff. This caused the flight crew to believe that the left engine was on fire. The flight crew's interpretation of the situation was likely influenced by a confirmation bias. Under normal circumstances and in isolation, the non-specific burning smell would have possibly been viewed as less critical. However, in the presence of the master warning flasher and engine fire warning annunciator, this smell was interpreted as confirmation of an engine fire. This led the flight crew to believe that the best course of action was to return to the airport as quickly as possible. During the rushed return to land, the flight crew did not refer to the emergency checklist.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

The flight crew believed that the left engine was on fire based on the combination of an illuminated engine fire warning annunciator and a perceived burning smell. This belief contributed to the speed with which the flight crew reacted and their urgency to land.

2.2 Factors associated with the urgency to land

2.2.1 Minimum sector altitude

The minimum sector altitude (MSA) provides a safety margin to protect aircraft and assure a clearance of a minimum of 1000 feet above all obstacles within a sector of a circle having a radius of at least 25 nautical miles (NM) centred on a radio aid to navigation or on a waypoint located near the aerodrome.

Two minutes before the occurrence, the reported weather consisted in a broken layer of clouds at 1460 feet ASL (1300 feet AGL) and an overcast layer at 2660 feet ASL (2500 feet AGL). The MSA for the area was 3100 feet ASL, which is the altitude that air traffic control (ATC) cleared the aircraft to fly. The aircraft levelled off at 2200 feet ASL, remaining below the MSA, during the return to CYYR.

ATC asked the flight crew if they would like a radar vector. The flight crew accepted ATC’s offer for vectors, and the controller cleared the aircraft to climb to 3100 feet ASL and to turn right to head north. The flight crew decided to remain below that layer of overcast cloud and stated that they had visual contact with the ground. However, the broken layer made it difficult for the crew to maintain constant ground contact throughout the vectors to final.

Visual cues are greatly reduced at night, particularly in areas with minimal ground lighting, making it more difficult to perceive terrain and judge proximity to the ground. Operating under reduced visibility conditions increases flight crew workload, especially when manoeuvring to remain in visual meteorological conditions by navigating around cloud layers to maintain ground contact.

Finding as to risk

If flight crews operating under instrument flight rules (IFR), at night, and in areas with low clouds and minimal ground lighting, elect to maintain visual reference to the surface rather than climb to the MSA when they experience an emergency on departure, there is an increased risk of controlled flight into terrain (CFIT).

2.2.2 Speed–accuracy trade-off

The urgency to return to the runway because of a perceived engine fire influenced the flight crew's prioritization of speed over task accuracy, resulting in a speed–accuracy trade-off. The flight crew’s prioritization of returning to the airport as quickly as possible manifested itself in the decision to continue in visual meteorological conditions and stay at a lower altitude, instead of following ATC instruction to climb to 3100 feet ASL. It also resulted in some notable sacrifices to task accuracy. Specifically, the flight crew shed some key tasks, including completing the checklists (engine fire in flight, engine shutdown, and one-engine inoperative approach and landing checklists), and as a result, the approach was not stable.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

The flight crew’s decision to expedite the return to the airport resulted in a speed–accuracy trade-off that contributed to the decision to operate below the MSA, the omission of the checklists, and deviations from the stabilized approach criteria.

2.3 Flight crew’s risk perception and decision making

During the final stage of the return to the airport, it is likely that the flight crew were experiencing high mental workload because of the perceived engine fire, time pressure, and unfamiliarity with the airport and terrain. When the flight crew acquired visual reference with the runway at 0.8 NM from it and at approximately 1350 feet ASL, they had to quickly decide whether to continue with the landing or to conduct a single-engine go-around. They decided to land.

At the 0.8 NM decision point, the flight crew were faced with the difficult task of evaluating multiple competing priorities and different potential outcomes. Some of these factors included the risk of conducting a single-engine go-around with an engine that was believed to be on fire compared to the risks of having to descend rapidly and land on a wet runway with reduced stopping capability due to only having one operational engine to apply reverse thrust.

Although both the options, to land or to conduct a go-around, had risk associated with them, the flight crew evaluated that of conducting a single-engine go-around with an aircraft potentially on fire as being a higher risk than landing the aircraft, despite not meeting the stabilized approach criteria. The flight crew may also have unconsciously incorporated their knowledge of runway length into their decision-making process, having just departed from the same runway. Thus, the flight crew may have overestimated the magnitude of the safety net provided by the long runway to land on and may have made a different decision had the runway been shorter.

The decision to land resulted in the aircraft crossing the threshold at 400 feet AGL (560 feet ASL) at a speed of 200 knots and at a rate of descent of over 2300 fpm. Based on the aircraft landing weight and configuration with flaps in the approach setting, with one engine inoperative, the target speed and approach speed is 103 knots. The standard operating procedures (SOPs) state that the aircraft speed is not more than Vref (landing reference speed) + 20 knots indicated airspeed and not less than Vref crossing the final approach fix or final approach waypoint inbound. The rate of descent was over 2300 fpm; however, the SOPs state that it should be no greater than 1000 fpm and that if an approach does require a sink rate greater than 1000 fpm, the flight crew should conduct a special briefing.

The aircraft touched down on the wet runway approximately 9075 feet from the threshold of Runway 08, with 1975 feet remaining, at a speed of 96 knots. The aircraft experienced hydroplaning and asymmetric thrust due to the use of reverse on the right engine. The aircraft manufacturer (Textron Aviation Inc.) did not have landing performance calculations for one-engine inoperable and asymmetric-reverse-thrust landing conditions. Post occurrence, Textron Aviation Inc. provided calculations based on a similarly configured aircraft; the calculations confirmed that the aircraft did not have enough distance to stop on the wet runway.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

The flight crew continued with the approach and landing with an excessive airspeed and rate of descent that exceeded the stabilized approach criteria. When combined with the wet runway and asymmetric reverse thrust, these approach parameters increased the landing distance required and resulted in the aircraft overrunning the runway.

2.4 Training

Flight crews receive annual training in flight simulators, which gives them the opportunity to practise abnormal and emergency procedures. The simulator used to train the occurrence flight crew was not equipped with the engine fire extinguisher control switches. Keewatin Air LP (Keewatin Air) operates 15 Beechcraft King Air B200s (King Air B200s), 5 of which are equipped with engine fire extinguisher systems. The flight crew, however, believed that only 2 aircraft were so equipped, and that the occurrence aircraft was not one of them, which highlights a gap in operational awareness of the fleet.

Keewatin Air SOPs provides specific guidance on the sequence in which a checklist should be completed. The SOPs consist of memory items specific to malfunctions, the pilot checklist for the malfunctions, caution advisory information, and landing precautions (reviewed with the approach briefing). The SOP for the engine fire in flight outlines the phraseology and aligns with the memory items in bold print on the pilot checklist, with exception of the fire extinguisher (if installed) to discharge. After the action of the firewall shut-off valve is confirmed closed and fire status is checked, the SOP states “MEMORY CHECK COMPLETE.” The flight crew will then state, “MAX CONTINUOUS POWER” and call for the “EMERGENCY ENGINE SHUTDOWN CHECKLIST” afterwards. On the following page, there are additional items for “memory checks if on fire (for aircraft equipped with fire bottles).” The actions are to confirm and actuate the left or right extinguisher. The order in which the SOP is written may cause the flight crew to miss the fire extinguisher item.

When flight crews are operating under high workload conditions (e.g., preparing for an emergency landing), they are likely to revert to their training when required to complete a sequence of events and/or make quick decisions. This observation is consistent with the recognition-primed decision-making model, which proposes that decisions are based on the first schema that is representative of the current environment. Although Keewatin Air provided its pilots training in ground school to identify the fire extinguishing system on the company’s fleet of aircraft, it is possible that the pilots, under high mental workload, automatically defaulted to their prior and well-rehearsed training on a simulator that was not equipped with a fire extinguishing system. Consequently, the task of activating the fire extinguisher may have never entered their schema for conducting an emergency landing with a possible engine fire.

With the master warning and engine fire annunciator illuminated, the flight crew completed the memory items but did not actuate the fire extinguisher. Whether this was their conscious choice stemming from the belief that activating the extinguisher was not required because no flames were visible, or an omission stemming from their unawareness that the aircraft was equipped with extinguishers, the result is that the extinguisher was not actuated.

Although the engine fire lens on the extinguisher system control switch was illuminated and would have been in the flight crew’s field of view, it is possible that they were functionally blind to it because of cognitive tunnelling. In other words, the pilots’ visual attention could have been captured and held by other visual stimuli on the glare shield (e.g., engine fire warning lights) with arguably higher visual salience.

Finding as to risk

If aircraft and flight simulators are equipped differently—for example, if engine fire extinguisher control switches are installed in one but not the other—there is a risk that flight crews may not be aware whether a system is available, especially under high mental workload conditions, such as an emergency.

3.0 Findings

3.1 Findings as to causes and contributing factors

These are the factors that were found to have caused or contributed to the occurrence.

- The flight crew believed that the left engine was on fire based on the combination of an illuminated engine fire warning annunciator and a perceived burning smell. This belief contributed to the speed with which the flight crew reacted and their urgency to land.

- The flight crew’s decision to expedite the return to the airport resulted in a speed–accuracy trade-off that contributed to the decision to operate below the minimum safe altitude, the omission of the checklists, and deviations from the stabilized approach criteria.

- The flight crew continued with the approach and landing with an excessive airspeed and rate of descent that exceeded the stabilized approach criteria. When combined with the wet runway and asymmetric reverse thrust, these approach parameters increased the landing distance required and resulted in the aircraft overrunning the runway.

3.2 Findings as to risk

These are the factors in the occurrence that were found to pose a risk to the transportation system. These factors may or may not have been causal or contributing to the occurrence but could pose a risk in the future.

- If flight crews operating under instrument flight rules, at night, and in areas with low clouds and minimal ground lighting, elect to maintain visual reference to the surface rather than climb to the minimum safe altitude when they experience an emergency on departure, there is an increased risk of controlled flight into terrain.

- If aircraft and flight simulators are equipped differently—for example, if engine fire extinguisher control switches are installed on one but not the other, there is a risk that flight crews may not be aware whether a system is available, especially under high mental workload conditions, such as an emergency.

4.0 Safety action

4.1 Safety action taken

4.1.1 Keewatin Air LP

Keewatin Air LP (Keewatin Air) conducted an internal investigation into this occurrence. The following corrective actions have been taken:

- Crew training review

The involved flight crew participated in a post-incident training evaluation. Their decision making, handling of the emergency, and adherence to stabilized approach criteria were reviewed in detail with the Flight Training Department. The flight crew was given additional ground school, reviewing the above topics. Additionally, the flight crew was given simulator training to emphasize the correct procedures to be flown during the occurrence flight and to ensure the flight crew was comfortable to return to the line. - Pilot training enhancements

Additional emphasis in recurrent training has been placed on:- management of abnormal approaches and enforcement of stabilized approach go-around criteria;

- performance planning on wet or contaminated runways, particularly with one engine inoperative;

- effective use of available stopping devices while minimizing directional control issues;

- incorporation of the accident into a crew resource management (CRM) case study that all Keewatin Air pilots receive;

- review of training and confirmation of the differences between aircraft during technical ground school.

Procedural improvements

Keewatin Air’s standard operating procedures (SOPs) and training programs have been updated to strengthen guidance on landing performance assessments during abnormal operations, and to ensure flight crews are prepared to make timely decisions when conditions exceed stabilized approach limits.

- Maintenance follow-up

- Quality control (QC) checks were completed on the following aircraft with no discrepancies noted: C-FMBO, C-GMBT, C-GKAO, C-FSPN, and C-GYSR.

- Keewatin Air has instituted ongoing proactive QC checks. If any issues are identified through these reviews, targeted remedial training will be provided to the personnel involved.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on 07 January 2026. It was officially released on21 January 2026.

![Figure 5. Occurrence aircraft’s 4-flame-detector fire detection system, with inset photo of the test switches (Source of main image: Raytheon Aircraft Company, Beechcraft Super King Air B200, B200 and B200C United Kingdom Maintenance Manual Supplement [05 August 1988], Fire Detection – Description and Operation, p. 2, with TSB annotations. Source of inset image: TSB) Figure 5. Occurrence aircraft’s 4-flame-detector fire detection system, with inset photo of the test switches (Source of main image: Raytheon Aircraft Company, Beechcraft Super King Air B200, B200 and B200C United Kingdom Maintenance Manual Supplement [05 August 1988], Fire Detection – Description and Operation, p. 2, with TSB annotations. Source of inset image: TSB)](/sites/default/files/2026-01/A24A0014-figure-05-ENG.jpg)

![Figure 8. Keewatin Air King Air 200 & B200 pilot checklist (Source: Keewatin Air LP, Beechcraft King Air Model 200 & B200 With Garmin G1000NXi [Revision 0], section E: Emergency procedures, p. E-2) Figure 8. Keewatin Air King Air 200 & B200 pilot checklist (Source: Keewatin Air LP, Beechcraft King Air Model 200 & B200 With Garmin G1000NXi [Revision 0], section E: Emergency procedures, p. E-2)](/sites/default/files/2026-01/A24A0014-figure-08-BIL_0.jpg)